1

The first thing Dr. Amy Goldberg told me is that this article would be pointless. She said this on a phone call last summer, well before the election, before a tangible sensation that facts were futile became a broader American phenomenon. I was interested in Goldberg because she has spent 30 years as a trauma surgeon, almost all of that at the same hospital, Temple University Hospital in North Philadelphia, which treats more gunshot victims than any other in the state and is located in what was, according to one analysis, the deadliest of the 10 largest cities in the country until last year, with a homicide rate of 17.8 murders per 100,000 residents in 2015.

Over my years of reporting here, I had heard stories about Temple’s trauma team. A city prosecutor who handled shooting investigations once told me that the surgeons were able to piece people back together after the most horrific acts of violence. People went into the hospital damaged beyond belief and came walking out.

That stuck with me. I wondered what surgeons know about gun violence that the rest of us don’t. We are inundated with news about shootings. Fourteen dead in San Bernardino, six in Michigan, 11 over one weekend in Chicago. We get names, places, anguished Facebook posts, wonky articles full of statistics on crime rates and risk, Twitter arguments about the Second Amendment—everything except the blood, the pictures of bodies torn by bullets. That part is concealed, sanitized. More than 30,000 people die of gunshot wounds each year in America, around 75,000 more are injured, and we have no visceral sense of what physically happens inside a person when he’s shot. Goldberg does.

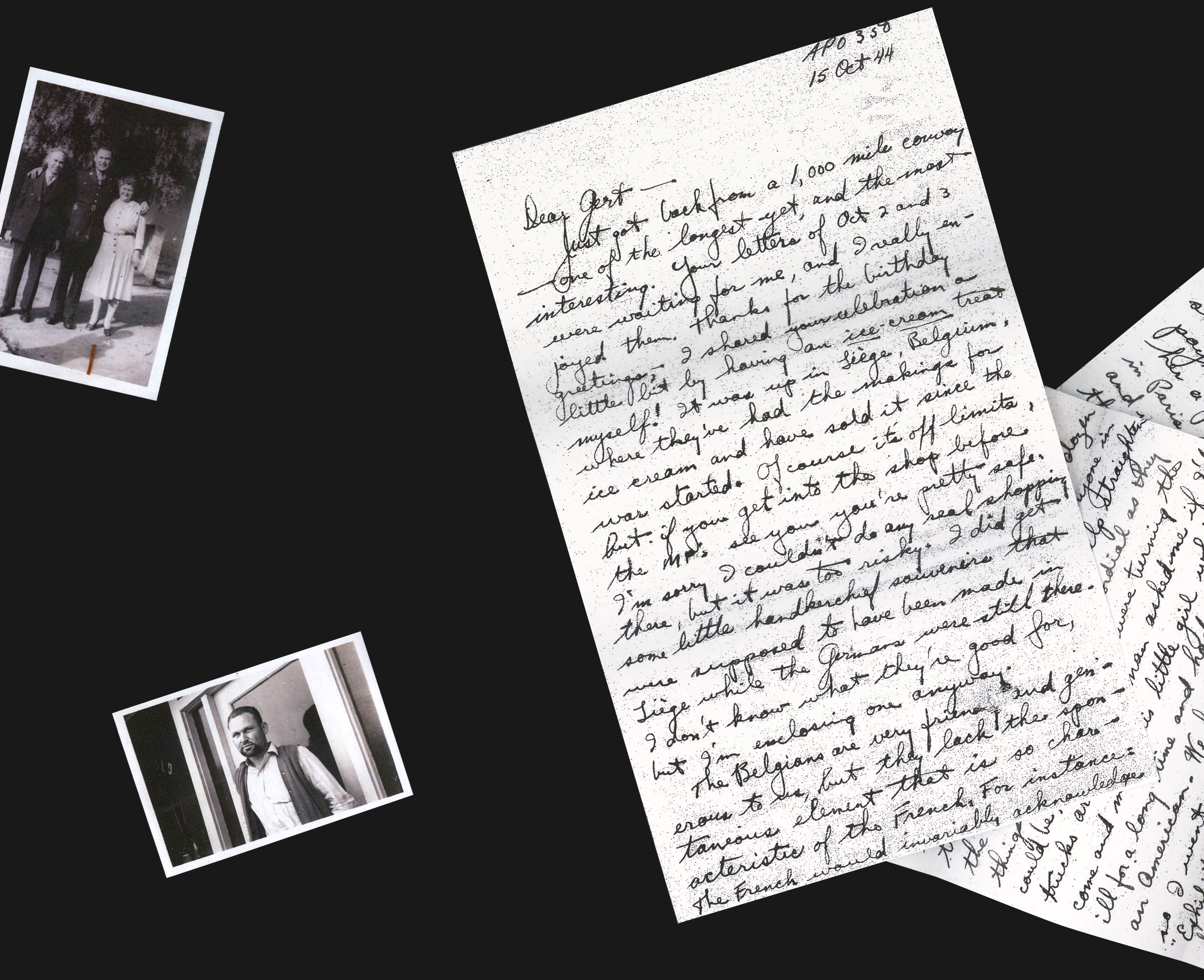

Even though Amy Goldberg has been treating gun patients for 30 years, the sense of horror has never completely gone away. On the cover: A bullet she keeps in her office. She pulled it out of a patient's heart during her residency.

Even though Amy Goldberg has been treating gun patients for 30 years, the sense of horror has never completely gone away. On the cover: A bullet she keeps in her office. She pulled it out of a patient's heart during her residency.

She is the chair of Temple’s Department of Surgery, one of only 16 women in America to hold that position at a hospital. In my initial conversation with her, which took place shortly after the mass shooting in Orlando, where 49 people were killed and 53 injured by a man who walked into a gay nightclub with a semi-automatic rifle and a Glock handgun, she was joined by Scott Charles, the hospital’s trauma outreach coordinator and Goldberg’s longtime friend. Goldberg has a southeastern Pennsylvania accent that at low volume makes her sound like a sweet South Philly grandmother and at higher volume becomes a razor. I asked her what changes in gun violence she had seen in her 30 years. She said not many. When she first arrived at Temple in 1987 to start her residency, “It was so obvious to me then that there was something so wrong.” Since then, the types of firearms have evolved. The surgeons used to see .22-caliber bullets from little handguns, Saturday night specials, whereas now they see .40-caliber and 9 mm bullets. Charles said they get the occasional victim of a long gun, such as an AR-15 or an AK-47, “but what’s remarkable is how common handguns are.”

Goldberg jumped in. “As a country,” Goldberg said, “we lost our teachable moment.” She started talking about the 2012 murder of 20 schoolchildren and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Goldberg said that if people had been shown the autopsy photos of the kids, the gun debate would have been transformed. “The fact that not a single one of those kids was able to be transported to a hospital, tells me that they were not just dead, but really really really really dead. Ten-year-old kids, riddled with bullets, dead as doornails.” Her voice rose. She said people have to confront the physical reality of gun violence without the polite filters. “The country won’t be ready for it, but that’s what needs to happen. That’s the only chance at all for this to ever be reversed.”

She dropped back into a softer register. “Nobody gives two shits about the black people in North Philadelphia if nobody gives two craps about the white kids in Sandy Hook. … I thought white little kids getting shot would make people care. Nope. They didn’t care. Anderson Cooper was up there. They set up shop. And then the public outrage fades.”

Goldberg apologized and said she wasn’t trying to stop me from writing a story. She just didn’t expect it to change anything.

2

The hospital’s main building is a nine-story tower on North Broad, the street that traces a north-south line through Philadelphia. If you think of Broad as the city’s spinal column, the hospital is about level with the heart. Stand on the sidewalk outside the hospital and look south on a clear day and you can see the pale marble and granite of City Hall, about 4 miles away, near Philly’s pelvis.

You can go to Temple for high-end elective surgery, like getting a knee replacement or a heart transplant, same as at any other major teaching hospital in the country. As Jeremy Walter, Temple Hospital’s amiable director of media relations, reminded me more than once, “Temple isn’t just a hospital that treats drug addicts and gun victims.” Still, it was founded 125 years ago by a Samaritan to provide free care, and that public-service mission persists. Some of the most violent blocks in the city are within a 4-mile radius of the hospital, and crime victims funnel in.

I first met Goldberg one weekday last summer, in the hospital lobby. I had arranged to stay and observe for 24 hours, accompanied every moment by Walter, who carried a trauma pager and a yellow folder of consent forms. The rule was that I could observe a surgery if the patient or a family member consented, and if I wanted to do an interview, the patient had to sign a form. Goldberg is 5 feet 2 inches tall, with a runner’s build. She wore a gray mock-turtleneck sweater with no sleeves. Her hair is short and there was a little gel in it that made it spiky. She explained that there are two main categories of trauma: blunt and penetrating. Blunt trauma is like a beating, a fall. Penetrating is a gun or stab wound. “Unfortunately we get a lot of penetrating traumas,” she said. Temple sees 2,500 to 3,000 traumas per year, around 450 of which were gunshot wounds in 2016.

The trauma pager buzzed shortly after noon. LEVEL 1 PED, it said—a pedestrian struck by a car. I followed Goldberg to the ER, and she disappeared behind a windowless set of double doors, into the trauma resuscitation area. A few moments later she emerged and waved me inside.

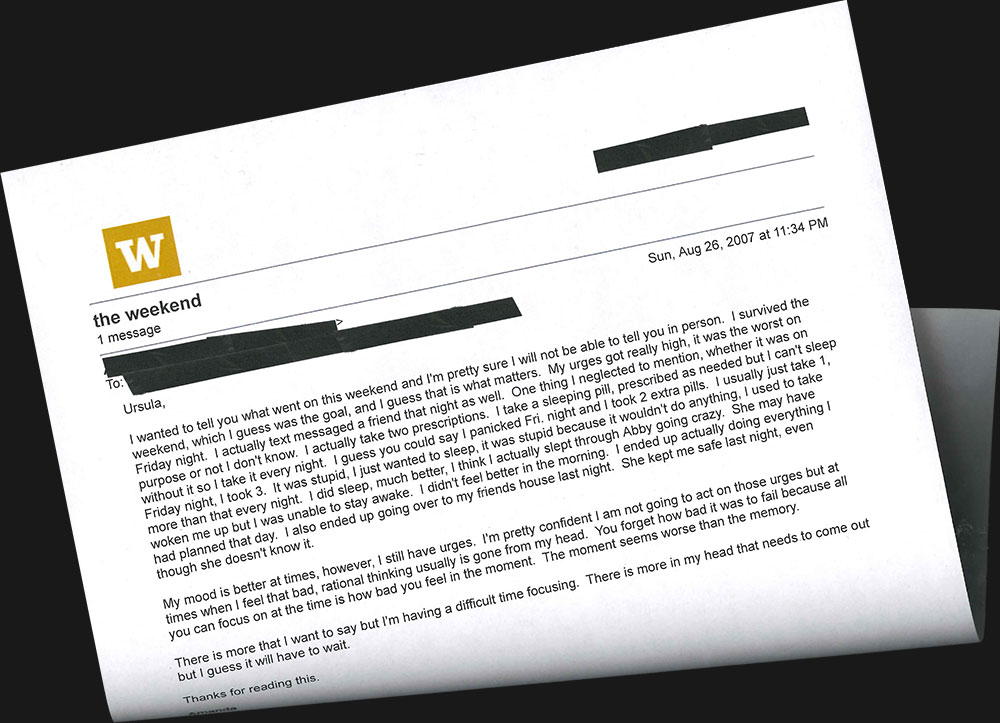

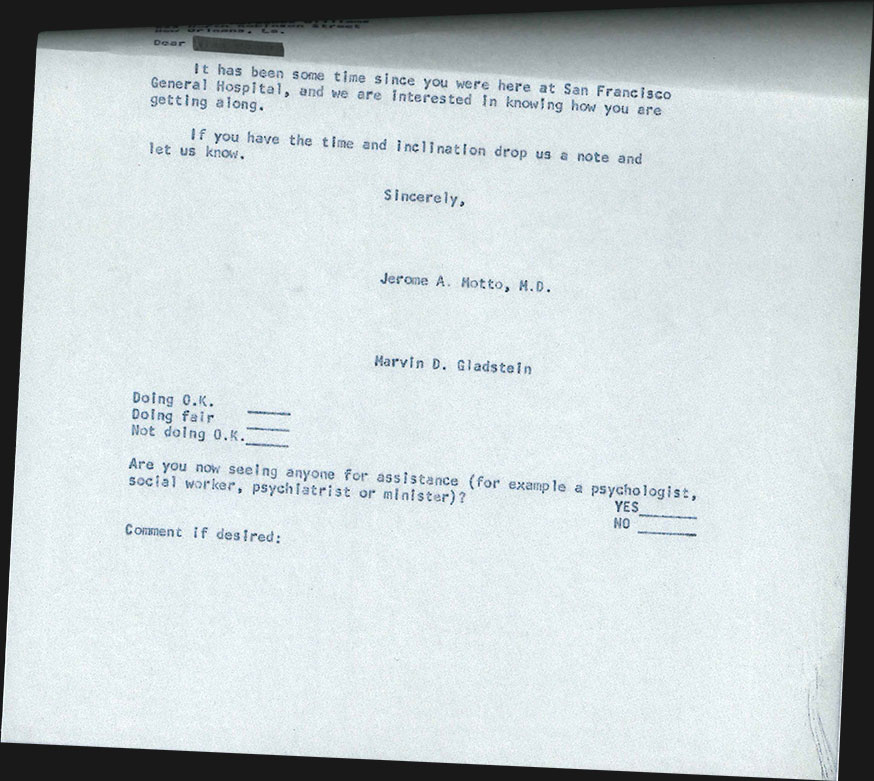

The trauma unit at Temple University Hospital, in a rare moment of calm.

The trauma unit at Temple University Hospital, in a rare moment of calm.

The trauma area is a rectangular room with three bays, each of which can accommodate two patients side by side when it’s busy. It’s an organized place—there are small trays on wheels for different surgical procedures, each tray holding a particular complement of instruments—but the tubes and cables snaking from poles and machines make it feel a bit chaotic to the untrained eye. The goal of a trauma surgeon is to limit the amount of time that a patient spends in a trauma bay, to stabilize the patient until he can be transferred for a CT scan or to the OR for surgery. The temperature in the room feels about five degrees hotter than in the rest of the hospital. The air doesn’t seem to move.

The pedestrian was awake but silent. This concerned Goldberg because by all rights he should have been screaming in pain. He looked to be in his late 20s. He had black hair and his shirt had been removed. He spoke Spanish. There was a laceration above his right eye and a small amount of blood on the sheets near his head. Goldberg and about 20 other doctors and nurses in blue scrubs clustered around him, checking vital signs, asking questions. Goldberg wore purple latex gloves. She tapped lightly on the patient’s left forearm with one hand. The arm was broken.

“No dolor?” she asked in Spanish. No pain? He shook his head. “Really?” she said. “No?”

Goldberg walked over to another doctor and said, “So are you troubled by the fact that he’s not screaming? He has an arm that’s so freaking broken and he’s not screaming.” She frowned. “I’m troubled by that.”

The patient’s vital signs appeared stable but Goldberg was worried about internal bleeding. A lack of pain could indicate a hidden injury. He needed a CT scan.

Staff wheeled the patient out of the trauma unit and into a nearby procedure room for the scan. Goldberg took off her latex gloves and threw them in a biohazard trash can. Two police officers had been observing from a distance with pens in hand and notepads open. One of the cops, a large man with a buzzcut, got Goldberg’s attention by saying, “Doc.”

“I’m Goldberg.”

The officer asked what the police should put down in their report for the patient’s condition. She said critical. This has been Goldberg’s policy for years, she explained to me as she exited the trauma bay and walked down a hallway toward the CT scanner. “I always make the patients critical until I know they’re fine. It’s a jinx thing.”

Goldberg is superstitious. On days when she’s on call, she shaves her legs. She can’t say why, she just started doing it years ago and now she will not deviate. She’s been wearing the same style of tan Timberlands for 15 years; her current pair, given to her by a colleague when she became chair of surgery, has the Temple logo inked on the heels. She parks her gray BMW in the same spot every time. “It’s so hard to take care of patients without making mistakes that you need every edge.” She recently hired a sports psychologist to talk to the residents about strategies for peak performance. Visualization. Positive self-talk. Breathing. For most of her career, she has stopped at the same Dunkin’ Donuts to order a large coffee with cream and two Sweet‘N Lows. A few years ago, the store stopped carrying Sweet‘N Low so she bought a box and left it there; they keep it under the counter for her. “It’s pink,” she told me once. “Sweet‘N Low is pink, Equal is blue, Splenda is yellow. And that is how you have to build a good system, believe it or not. So nobody makes a mistake.”

Goldberg, a superstitious sort, has been wearing Timberlands on the job for 15 years.

Goldberg, a superstitious sort, has been wearing Timberlands on the job for 15 years.

In the hallway next to the ER, she opened a door and I followed her into a small darkened room where six young doctors sat at computers. A window looked into the bay next door that held the CT scanner. “Billie Jean” played at low volume from a tinny speaker. Goldberg watched through the window as staff moved the patient from his gurney onto the bed of the machine. He cried out. Goldberg said, “That seems more appropriate.” Now they gave him some pain medicine. She looked at me and winced. “He has a broken humerus. I mean, you can feel it.” She streaked the thumb of her right hand against her fingers. “It’s one of my least favorite injuries. You can feel the bones rubbing together.” The CT scan showed some clotted blood in the patient’s head, appearing on the screen as patches of white. Goldberg ordered some additional scans.

When a shooting comes across the trauma pager, the code is GSW. There were no GSWs that night, only assaults. One patient was an older man who had been beaten up and complained of stomach pain. Another had been stabbed in the abdomen during a fight. His assailant was brought in too, in handcuffs, a white-haired man in a red T-shirt, his left eye bloodied and swollen shut.

The injuries weren’t life-threatening. Goldberg attended to the patients in the trauma unit. When she wasn’t there, she went on rounds, taking the elevator up to the eighth and ninth floors to check in with patients recovering from earlier traumas. She walked fast from one place to the other and I would lose her sometimes behind corners and doors and she’d have to double back for me. These are busy shifts even when there aren’t a lot of fresh traumas coming in. During a down moment Goldberg mentioned that she was thinking about scaling back her call schedule now that she’s chair of surgery, with large administrative and educational responsibilities. “I’ve been doing this 30 years,” she said. “Do I need to be on call? Do I need to do Saturdays?”

The pager stayed quiet overnight and through late morning, when Goldberg’s call shift ended. I arranged to return and shadow her again on her next shift, in two days. I left the hospital before lunch. The following morning the trauma pager blew up. LEVEL 1 GSW TO CHEST. LEVEL 1 MULTIPLE GSW TRANSFER FROM EPISC (Episcopal Hospital). LEVEL 1 SECOND GSW MALE.

3

Goldberg didn’t know much about guns or gun violence until she got to Temple. She grew up in the quiet Philadelphia suburb of Broomall. Her father owned a dairy business in the city, her mother was a schoolteacher. She was an intense kid who really believed the religious ideas she was learning at Jewish summer camp “in a big, bad way.” When she was 11, she woke up to see a light through her window and feel a tremor underfoot, and she wondered if it was God’s doing.

She went on to study psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. She particularly loved anatomy. “It’s a miracle,” she told me. “The creation of a person, you know. It’s the heart beating and the lungs bringing air. It is so miraculous.” Surgery, for Goldberg, was a way of honoring the miracle. And trauma surgery was the ultimate form of appreciation, because a surgeon in trauma experienced so much variety. She might be operating on the carotid artery in the neck, or the heart in the chest, or the large bowel or small bowel in the abdomen, or the femoral artery in the thigh, at any given moment, on any given night.

In her first or second year of residency at Temple, when she was in her mid-20s, she helped treat a young boy who had been shot in the chest by his sibling who picked up a loaded gun that was lying around. The doctors couldn’t save him. The senselessness made her so angry. Goldberg listened as a senior resident informed the boy’s mother. “I’m sorry,” the resident said, “he has passed.” The mother didn’t react; she didn’t seem to understand what she had just heard. Goldberg spoke up. “He died. We’re so sorry. He died.” It was a lesson: Be direct. “You have to find a very compassionate way of being honest,” she said.

“You think you know what happens here? Because I thought I knew. But there’s nothing that can prepare you.”

She finished her residency in 1992 and decided to stay at Temple, and the feeling of wrongness only intensified. There was a teenage boy in August 1992 who was shot in the heart. His heart stopped beating. Goldberg revived it. He lived. But some weeks later he came in again, with a shooting injury to his brachial artery, in the upper arm. He almost bled out, almost died again, but the surgeons got him back, again. “And then of course the third time he came in, he was shot through the head, and he was dead,” Goldberg said.

She started thinking that Temple should find a way to intervene—to try to talk to patients while they’re in the hospital so they would never need to come back. But she didn’t have the authority yet. She was just a trauma surgeon, a good one, and getting better. She had good hands and good judgment and a methodical approach to the craft. And as five years stretched into 10, and 10 into 20, Goldberg built up a deep well of experience in doing the things that are necessary to save the lives of gun victims, the things that are never shown on TV or in movies, the things that stay hidden behind hospital walls and allow Americans to imagine whatever they like about the effects of bullets or not to imagine anything at all. “You think you know what happens here?” Scott Charles asked me. “Because I thought I knew. But there’s nothing that can prepare you for what bullets do to human bodies. And that’s true for pro-gun people also.”

The main thing people get wrong when they imagine being shot is that they think the bullet itself is the problem. The lump of metal lodged in the body. The action-movie hero is shot in the stomach; he limps to a safe house; he takes off his shirt, removes the bullet with a tweezer, and now he is better. This is not trauma surgery. Trauma surgery is about fixing the damage the bullet causes as it rips through muscle and vessel and organ and bone. The bullet can stay in the body just fine. But the bleeding has to be contained, even if the patient is awake and screaming because a tube has just been pushed into his chest cavity through a deep incision without the aid of general anesthesia (no time; the patient gets an injection of lidocaine). And if the heart has stopped, it must be restarted before the brain dies from a lack of oxygen.

It is not a gentle process. Some of the surgeon’s tools look like things you’d buy at Home Depot. In especially serious cases, 70 times at Temple last year, the surgeons will crack a chest right there in the trauma area. The technical name is a thoracotomy. A patient comes in unconscious, maybe in cardiac arrest, and Goldberg has to get into the cavity to see what is going on. With a scalpel, she makes an incision below the nipple and cuts 6 to 10 inches down the torso, through skin, through the layer of fatty tissue, through the muscles. Into the opening she inserts a rib-spreader, a large metal instrument with a hand crank. It pulls open the ribs and locks them into place so the surgeons can reach the inner organs. Every so often, she may also have to break the patient’s sternum—a bilateral thoracotomy. This is done with a tool called a Lebsche knife. It’s a metal rod with a sharp blade on one end that hooks under the breastbone. Goldberg takes a silver hammer. It looks like—a hammer. She hits the top of the Lebsche knife with the hammer until it cuts through the sternum. “You never forget that sound,” one of the Temple nurses told me. “It’s like a tink, tink, tink. And it sounds like metal, but you know it’s bone. You know like when you see on television, when people are working on the railroad, hammering the ties?”

“It’s just the worst,” Charles told me. “They’re breaking bone. And everybody—every body—has its own kind of quality. And sometimes there’s a big guy you’ll hear, and it’s the echo—the sound that comes out of the room. There’s some times when it doesn’t affect me, and there are some times when it makes my knees shake, when I know what’s going on in there.”

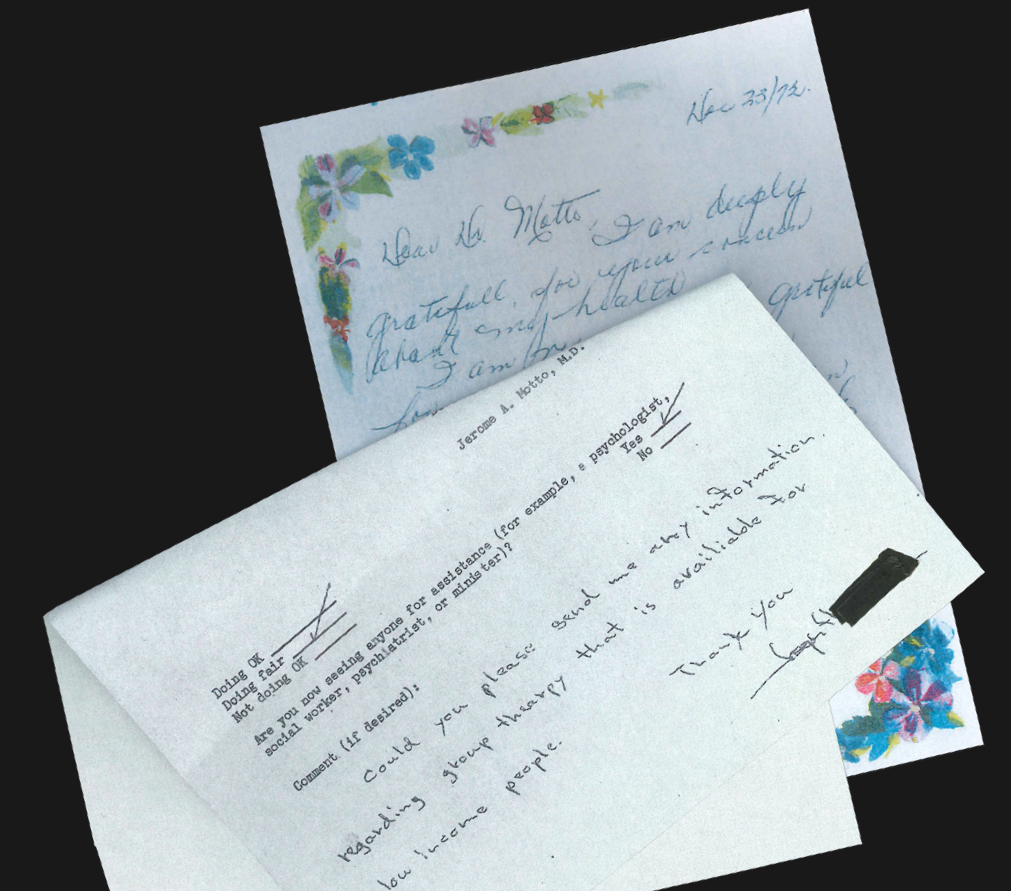

Some of the simple tools surgeons employ in the trauma bay, including the Lebsche knife and silver hammer used to break the sternum while opening chest cavities.

Some of the simple tools surgeons employ in the trauma bay, including the Lebsche knife and silver hammer used to break the sternum while opening chest cavities.

Now the chest is open, and Goldberg can work. If the heart has stopped, she can try to get it beating again. This may involve open cardiac massage—literally holding the heart in her hands and massaging it to get blood flowing up to the brain again. If there’s bleeding in the cavity, she can control it by putting a metal clamp on the heart or on the lung. She can also clamp the aorta, the largest artery in the body, so that instead of the blood going down into the bowels, where it’s needed less, the blood goes up to the brain.

“These crossing bullets are just so challenging,” she said. “Where is the injury? Is it in the chest? Is it in the abdomen? You’re down there, looking, and sometimes you find it, and sometimes you don’t. And sometimes it just really hurts as you work your way through.” She meant that it hurts when patients suffer. Hurts them and hurts her.

There are some gun victims who die quickly, right there in the trauma bay, or soon after being transferred up to the OR. Others develop cascades of life-threatening complications in the following days that surgeons race to manage.

Goldberg said she saw a movie a few years ago that captures what it’s like to operate under these conditions. It was a documentary about the 33 Chilean miners who were trapped underground for months in 2010. “They interviewed them all. And the miner that had the hardest time down there was the youngest guy. Not the oldest guy. It was the youngest guy. And they said, why? Why did you have such a hard time? And he said, God and the Devil were with me.” Goldberg thought that was perfect. “That’s what I had been searching for, for years, in how you feel in the operating room. God and the Devil are with you. You start a case. A young person. Shot. They come in talking. You go upstairs. They have this devastating injury. The Devil. You suck. You’re gonna kill this guy. You call yourself a good trauma surgeon. You’re the worst. And you just plow ahead and plow ahead and plow ahead. You find what’s injured. You control it. God. Oh, you are the best. You’ve done a great job. Then you’re working. You find another injury you didn’t expect. You suck, you suck, you suck.”

During trauma surgery, tissue in the lower extremities can die, causing gangrene, in which case surgeons might have to amputate the leg at higher and higher points, first at the shin, then at the knee, then at the thigh.

It’s possible for a surgeon to get distracted by the wrong wound. The most dangerous wounds don’t always look the worst. People can get shot in the head and they’re leaking bits of brain from a hole in the skull and that’s not the fatal wound; the fatal wound is from another bullet that ripped through the chest. One patient a few years ago was shot in the face with a shotgun at close range over some money owed. He pulled his coat up over his mangled face and walked to the ER of one of Temple’s sister hospitals, approaching a nurse. She looked at him. He lowered the coat. The nurse thought to herself what you might expect a person to think in such a situation: “Daaaaaamn.” He was stabilized, then transferred to Temple. He lived.

The price of survival is often lasting disability. Some patients, often young guys, wind up carrying around colostomy bags for the rest of their lives because they can’t poop normally anymore. They poop through a “stoma,” a hole in the abdomen. “They’re so angry,” Goldberg said. “They should be angry.” Some are paralyzed by bullets that sever the spinal column. Some lose limbs entirely. During trauma surgery, when the blood flow is redirected to the brain and heart by an aortic clamp, blood goes away from other areas, and tissue in the lower extremities can die, causing gangrene, in which case surgeons must amputate the leg at higher and higher points, first at the shin, then at the knee, then at the thigh, to stay ahead of the necrotic tissue as it spreads. The femur bone may have to be disarticulated—removed entirely from the socket, and discarded. There was a woman several years ago whose boyfriend shot her in the leg. The bullet clipped the femoral artery and she bled. Goldberg was on call that day. She had to amputate the woman’s legs to save her life. “I’m so haunted by that,” she said.

Eighty percent of people who are shot in Philadelphia survive their injuries. This statistic surprises people when they hear it. They tend to think that when people get shot in the belly or the chest or the face, they die. But the reality is that people get shot and then they are going to survive, because trauma surgeons are going to save them, and that’s when the real suffering begins.

4

Rafi Colon was shot once in the abdomen with a 9 mm handgun during a home invasion in September 2005. The bullet tore through his intestines. Trauma surgeons at Temple had to open his abdomen to repair the injuries, but fistulas developed, holes that wouldn’t heal, and until they healed, the incision couldn’t be closed. He spent the next 11 months in the hospital, immobilized in bed, with an open wound down the front of him that had the circumference of a basketball. It got to the point where it was a normal thing for him to look down and think, oh, those are my intestines, there they are.

“It became second nature,” he told me recently over lunch at a Panera Bread in the Philly suburbs. “It wasn’t like a gruesome thing.” The holes in his intestines leaked stomach acid and burned away the surrounding tissues and skin, leaving less skin available to eventually stretch over the wound and close it. Colon learned to sop up the excess acid from his exposed intestines with gauze pads and later with a machine that sucked the acid through a tube. When his friends came to visit, they had a hard time looking at him. He messed with them once by asking a buddy to get him a Rita’s water ice, Philadelphia’s version of a snow cone. He knew what would happen when he ate it. The water ice was red, the Swedish Fish flavor from that summer, and 30 seconds after he swallowed it, the red water ice came oozing out of the hole in his intestine. His friends bolted.

Over the course of his long recovery, from the fall of 2005 into the spring and summer of 2006, Colon got a feel for the rhythms of the Trauma Service. Lying there in the bed, he occupied himself by counting the number of times each day that trauma codes were announced over the PA system. It seemed like the busiest times were Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights. He’d ask the doctors, how many yesterday, was it 17? “They’d say, ‘No, 18.’” He could tell when the residents were stressed out by how many Diet Cokes they drank. There were days when the doctors were so busy with fresh traumas that they didn’t make rounds until 7 or 8 at night. “They would say, ‘Yeah, it was a busy day.’ I’d be like, ‘Yeah, I heard.’”

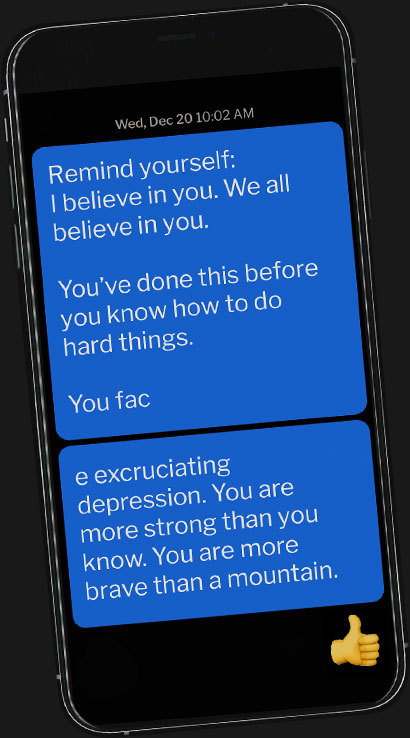

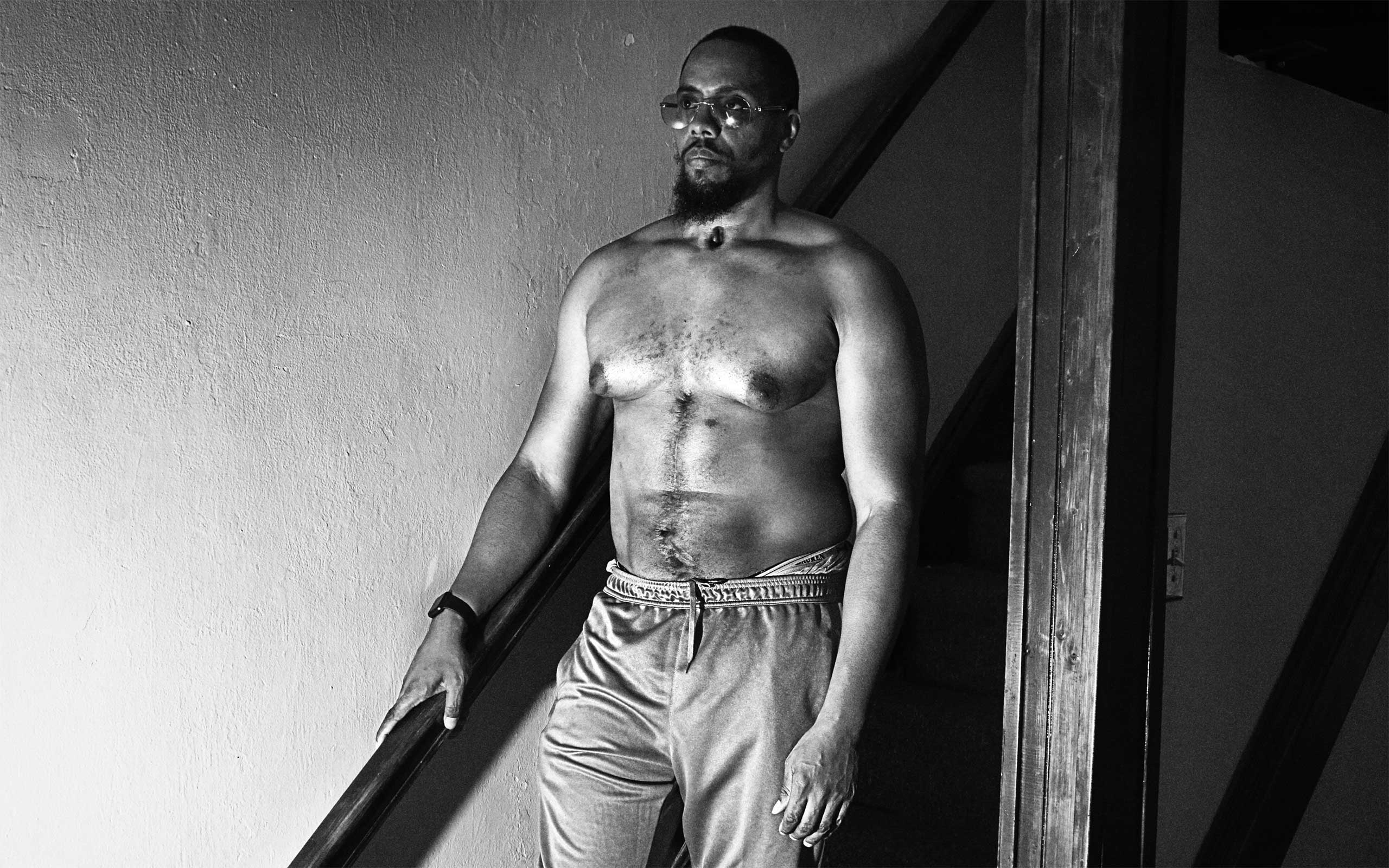

Rafi Colon in his stairwell at home. Though his neck and stomach scars are still visible years after being shot, he can't terrify friends with his water ice trick anymore.

Rafi Colon in his stairwell at home. Though his neck and stomach scars are still visible years after being shot, he can't terrify friends with his water ice trick anymore.

It ultimately took 14 surgeries to repair the damage done by one bullet. Temple’s surgeons stretched his abdominal wall closed with the help of some muscle from another part of his body and an artificial mesh. If you see Colon today, the only way you can tell he was wounded is that he walks with a minor tilt; he calls it “my Keyser Söze limp.”

Goldberg was part of the team of doctors who cared for him. They talked about muscle cars and sports. (She liked the Eagles; his team was the Giants.) He remembers that she was the doctor who would notice when he was feeling despair and let him eat a little something that the nurses wouldn’t necessarily allow, like a small chip of ice, or sometimes a piece of candy. He couldn’t eat normally—he was being fed intravenously—but “the fact that I could get a piece of ice, it was like heaven.”

She has gotten more sensitive over the years, she said. When you’re a young trauma surgeon, you’re developing skills, like how to put a bowel back together. Her medical training was all about learning to operate, to recognize the kinds of patterns that she now teaches to students and young doctors. I once saw her give a lecture to 11 medical students who had just completed their surgical rotation. Goldberg diagrammed anatomy and formulae on a whiteboard and asked questions about how the students would diagnose various hypothetical patients. But she also asked the students to share their experiences with patients and their feelings about those cases. One student spoke about stitching together the chest of a young shooting victim who had died after surgeons attempted to resuscitate him in the trauma area; the student’s first thought was that he was excited to practice stitching a chest, then he felt guilty for being excited. Another student recalled being surprised when a patient asked for his business card even though he was just a lowly medical student. “Yeah,” Goldberg said. “He trusted you.”

Often when Goldberg meets a shooting victim, it turns out she once treated a sibling, parent, cousin or friend. “I’m a family doctor, a little bit, because I’ve been here so long,” she said. One day at the hospital, I saw her go on rounds, meeting with patients in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) on the ninth floor. A sign on a bulletin board said WELCOME TO SICU! YOUR HEALING STARTS HERE! The letters were surrounded by gold stars.

Talking to patients seemed to energize Goldberg. She was alternately lighthearted and serious. The patients were uniformly docile and tired. They were on pain medication that slowed their speech. The first patient, shot in the neck, was a young man accompanied by his girlfriend, who sat next to him on the bed with an expression of concern. “When I was shot, I fell on my face,” he said. The second patient was older. A tube to drain fluids was snaking out of his chest. He held out a trembling left hand and smiled. “A little bit of the shakes,” he said. Goldberg told the man he was scheduled to be released the following Monday. He had been caught in some kind of crossfire. “We will miss you,” Goldberg said, “but there comes a day.”

“Cut the umbilical cord, huh?” he said, and laughed softly.

Goldberg descended to the eighth floor to meet with another gun victim. She knocked on his door and said hello in her friendly voice. There were two large men inside the room in T-shirts and shorts. She assumed they were his family, but when she entered, the men rushed over to her and said that the patient was a suspected shooter himself. They were plainclothes cops, guarding him.

“I don’t want to know,” she said. “It’s better if I don’t know.”

She went over to the side of the patient’s bed as the cops watched and said she was Dr. Goldberg and she wanted to explain what was happening and help him if he needed anything.

He looked young. He seemed afraid. There was an open wound in his chest, a vertical incision from below his nipples to his belly button, rising and falling with his breath. Surgeons had needed to remove one of his kidneys, his spleen and part of his stomach to repair the damage of the bullet and save his life. After the surgery the tissue swelled, which happens sometimes, and they couldn’t immediately stitch the incision closed, so they had to leave it open. The edges of the wound were pink and raw.

Goldberg reached out and held his left hand in her hand while telling him what organs he’d lost.

“You don’t need your spleen. You do need your kidney,” she said. “But luckily, God gave us two.”

He nodded slightly. She asked how he was feeling. All he said was, “Pain.”

Goldberg said they would try to help with that and rubbed her fingers across his hand in a gesture of tenderness.

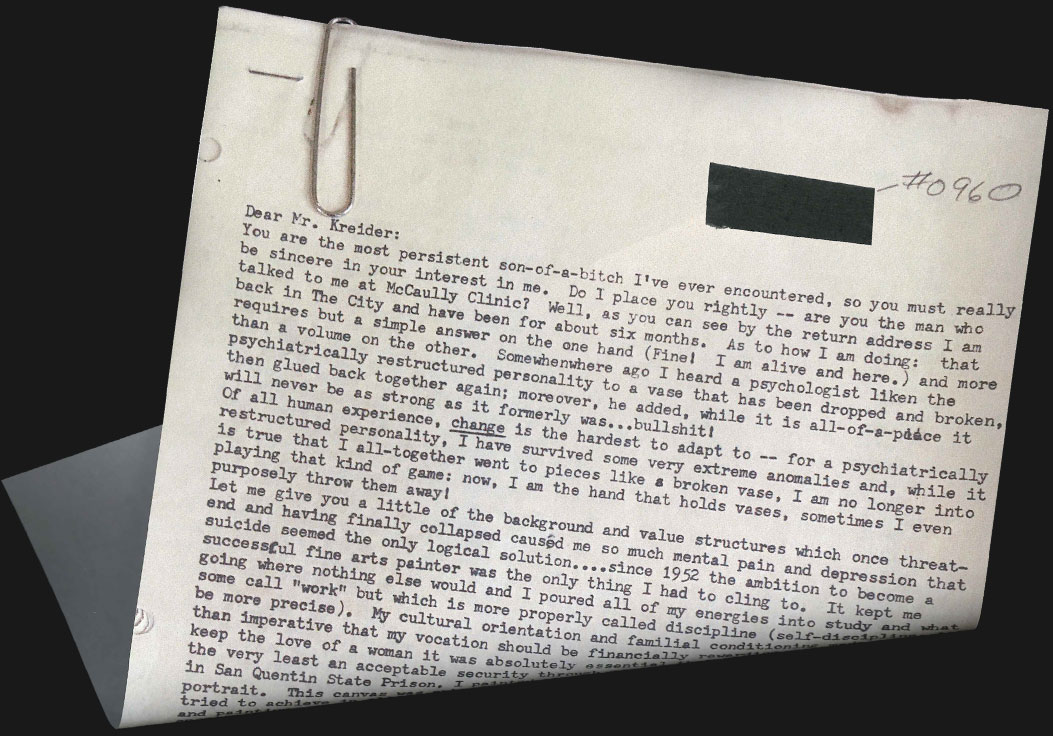

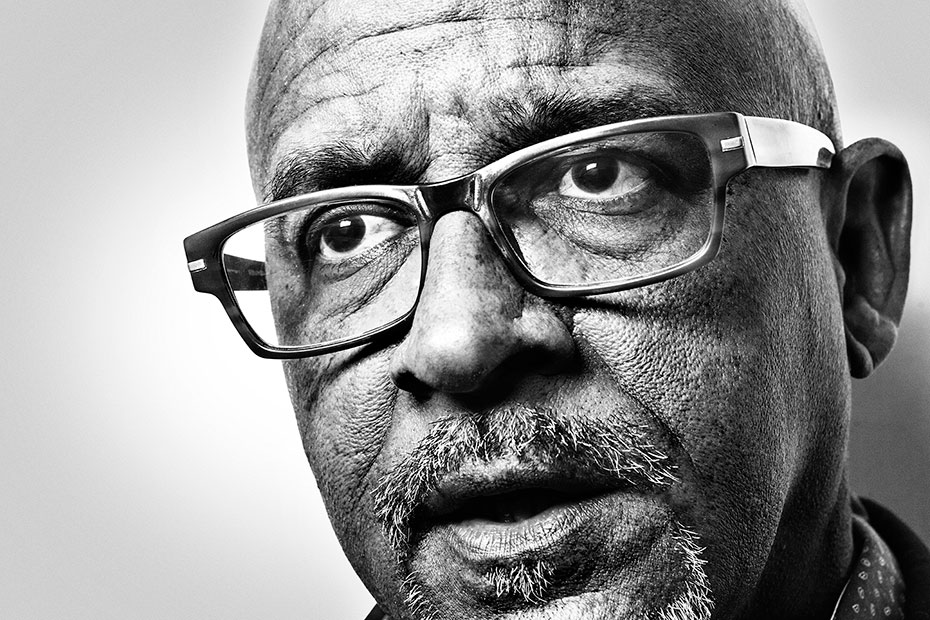

Gunshot victim Lamont Randell, shot twice during a robbery, begins his long recovery process.

Gunshot victim Lamont Randell, shot twice during a robbery, begins his long recovery process.

5

The key distinction for Goldberg isn’t innocent or guilty, it’s rational or irrational. Gun violence is irrational, there’s no pattern to it. Police statistics show that shootings decrease in the cold winter months and pick up when the weather warms, but any given trauma shift in the winter can be busy and any shift in the summer perfectly quiet.

Goldberg has always found the senselessness of violence frustrating, and when she was promoted to chief of trauma 15 years ago, she started thinking about how to engineer some control, to help patients “above and beyond just being a trauma surgeon.” She imagined a comprehensive approach to prevent shootings and keep patients from showing up in a trauma bay in the first place. She knew this would involve talking to people in the community, but she also knew she was a flawed messenger. “Who’s going to listen to this white Jewish girl say that guns in the inner city aren’t good for you? Nobody’s going to listen to me say that. I wouldn’t listen to me.” She went looking for help, and found Scott Charles.

A big, energetic guy with glasses and a master’s degree in applied positive psychology from the University of Pennsylvania, Charles has been working to reduce youth violence since 1988. When he was growing up in Sacramento, two of his older brothers were shot and his sister committed suicide with a gun, and at 19 one of his best friends was shot and killed. He moved to Philadelphia when his sociologist wife got hired by Penn, and two years later, he joined a nonprofit that designed service-learning projects in public schools. Some of his students from North Philly started collecting the stories of families who had lost children to gun violence, which is how Charles made the connection to Goldberg—Temple had treated one of the victims, Lamont Adams, a 16-year-old from North Philly who was shot and killed in 2004 after a false rumor was allegedly spread about him.

Goldberg hosted a tour for Charles and his students, inviting them into the trauma unit and explaining what gun patients experience there. She was immediately impressed by the way he dealt with the kids. She told him she’d create a new outreach position for him at Temple, that she’d get up “in people’s faces” until she made sure it happened.

“She said, ‘Don’t go anywhere else,’” Charles recalled. “‘I’m going to write you a check for one year of your salary. If I don’t get this position for you, you can cash the check, it’s yours, and take another job.’ And I was like—this white lady’s crazy. My wife was like, who’s this lady who keeps calling you at 11 o’clock at night? ‘It’s this crazy doctor.’”

Charles accepted, joining Temple in August 2005, and since then he and Goldberg have developed a suite of ambitious programs in collaboration with other Temple doctors and staff. “The thing that allows us to do so much of this is she carries a big stick,” Charles said. “Who was going to get in her way?”

There are three programs aimed at preventing violence before it happens. Cradle to Grave is an expansion of that first tour Charles took at Temple. He brings groups of kids and adults into the trauma area and shows them how surgeons save gun patients. He has his own copies of the various surgical instruments for demonstration purposes, removing them from a travel bag: chest tube, rib-spreader, hammer, Lebsche knife. He introduces the visitors to Goldberg if she’s available. He tells the story of Lamont Adams, asking a volunteer to pretend to be Lamont and then placing a circular red sticker on the location of each of Lamont’s 24 bullet wounds (entry and exit). On his chest. His abdomen. His thigh and arms. And most disturbing of all, the two bullet wounds on his hand, a sign that Lamont was trying to shield his face from the bullets at close range.

Charles also runs the Fighting Chance program, a series of training sessions for community members, where doctors show people in neighborhoods how to give first aid to gunshot victims, to apply tourniquets and stop blood loss in the seconds immediately following a shooting, before the EMTs or police arrive. Recently, Charles has also become a sort of Johnny Appleseed of gun locks, handing them out to parents who want to keep their children from getting hurt in accidents. He keeps boxes of them at the hospital and distributes the locks with no questions asked. Sometimes he lugs them to subway stations and offers them to commuters.

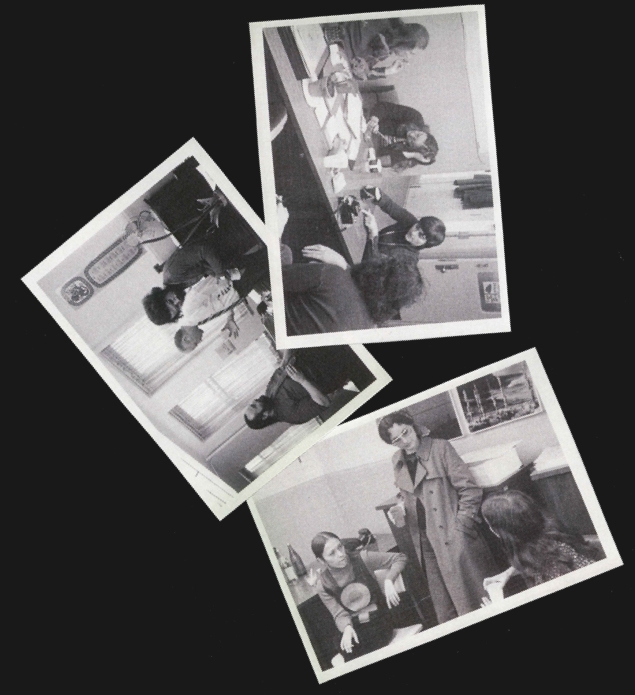

When Goldberg first saw Scott Charles talk to a group of children, she knew she needed him on her team.

When Goldberg first saw Scott Charles talk to a group of children, she knew she needed him on her team.

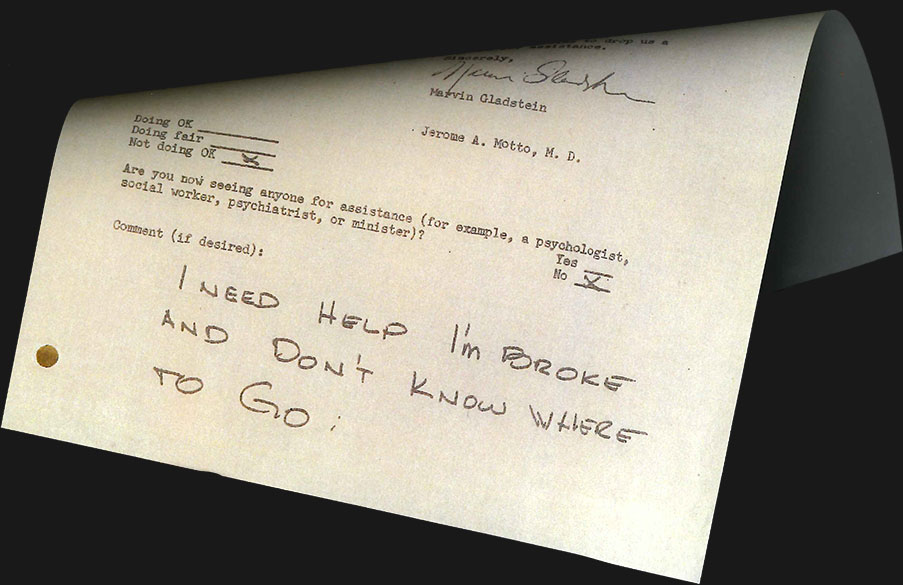

That’s prevention. Temple has also created an intervention component, called Turning Point, where shooting victims get extra counseling while they’re still in the hospital. “They come in, they’re very scared,” Goldberg said. “‘Am I gonna die? Where’s my Mom?’ Then, as soon as they would recover, they would not be so scared anymore, which maybe wasn’t good.” So if a victim is between 18 and 30 years old, he’s offered a series of supports in addition to the usual visits with Charles and a social worker. Temple asks the patients if they want to talk to a trauma survivor. And they are given an opportunity to view a video of their own trauma-bay resuscitation. (The surgeries in the trauma area are videotaped for quality control.) About half say yes. Charles shows them the video. They get psychological counseling for any PTSD symptoms, as well as case management services to help them get high-school diplomas or jobs.

Turning Point was initially controversial within the hospital. Some doctors thought it was cruel to show patients videos of their own surgeries, especially patients who had done nothing wrong. But Goldberg argued that she wasn’t judging anyone’s past or even asking about it. “The only way I know how to deal with a problem is, let’s break it down. Let’s try to educate,” she said.

Breaking it down has involved doing science. Goldberg and her team have needed to gather data about questions that have never been rigorously answered, a common situation when it comes to gun violence. For instance, when a paramedic first finds a gun or stabbing victim, nobody knows if it’s better to administer IV fluids and put a tube down the victim’s throat on the spot, or if the medic should simply race the victim to the hospital. Trauma surgeons have long suspected that the latter option is preferable—most shooting victims actually arrive at Temple in the back of police cruisers, a practice the cops call “scoop and run”—but there has never been a long-term randomized study.

So Temple launched one. It’s called the Philadelphia Immediate Transport in Penetrating Trauma Trial (PIPT), an elaborate undertaking that has involved close coordination with emergency personnel and also dozens of community meetings where doctors explained how the study works (over the next five years, some victims of penetrating trauma will receive immediate transport and some won’t) and how people can opt out of the study (by wearing a special wristband). In that same spirit, Goldberg has been gathering data on the Turning Point program. For years, patients have been randomized into a control group and an experimental group. One group gets typical care and the other gets Turning Point, and then patients in both groups answer a questionnaire that quantifies attitudes toward violence.

In November the hospital published its first scientific results from Turning Point, based on 80 patients. According to Temple’s data, the Turning Point patients showed “a 50% reduction in aggressive response to shame, a 29% reduction in comfort with aggression, and a 19% reduction in overall proclivity toward violence.” Goldberg told me she was proud of the study, not only because it suggested that the program was effective, but also because it represented a rare victory over the status quo. Turning Point grew out of her experience with that one patient in 1992, the three-time shooting victim who died the third time. It took her that long to get the authority, to gather the data, to get it published, to shift the system a little bit.

Twenty-four years.

6

Each time I went to the hospital, I asked Goldberg what else was going on with her aside from work. She usually talked about running. She likes to run along the Schuylkill River while listening to music and thinking about nothing at all. She competes in a few half-marathons a year.

I never learned much about Goldberg’s personal life. She lives alone in an apartment in Center City. She has a rowing machine there and access to a treadmill in the building’s gym. Her religious faith is still strong—it’s not that she goes around talking about it, she told me, it’s just that she has worked for 30 years in trauma and seen a lot of death, and it’s hard to do that and not feel something about God. I noticed one day she was wearing a white Lokai bracelet, a ring of plastic capsules said to contain mud from the Dead Sea and water from Mount Everest. “The highs and the lows, to stay even-keeled,” she said. “I probably need 10 of them, five on each hand.”

The major non-running events in her life tend to be awards ceremonies. She has reached the point in her medical career where people gather and say nice things about her, and there are plates of olives and prosciutto. Her med-school alma mater, Mount Sinai in New York, recently invited her to give a special lecture at Grand Rounds, a hallowed medical tradition. On March 16 Temple threw a party for her “investiture,” a ceremony where she passed from being merely the chair of surgery to being the George S. Peters MD and Louise C. Peters Chair in Surgery. Endowed chairs at universities are a big deal. Past colleagues from all over the country came to speak about her qualities. One compared her to Teddy Roosevelt’s famous Man in the Arena, “whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood … who spends himself or herself in a worthy cause.” (“Herself” is not actually a part of Roosevelt’s quote, but the guy modernized it for Goldberg.) She gave a brief acceptance speech focusing on the importance of teamwork to medical excellence. She said she used to dream about being a sports coach, and now she’s coaching the next generation of surgeons. As she once put it to me, “One of us can’t give perfect care. But together, maybe, we can give perfect care.”

In a perverse way, the more efficiently Goldberg does her job inside the hospital, the more invisible gun violence becomes everywhere else.

One of the speakers at the investiture called Goldberg a “realistic idealist,” and when I saw her later, she said she’d been thinking about the phrase. At first it surprised her that people saw her that way, but she realized it captured something true. “When I get angry, and hurt,” she told me, “it’s because I can still be a little naïve.” Even after all this time, the sense of horror she first experienced as a resident treating gun patients has never completely gone away.

One evening when I was at the hospital, I saw what she meant. Two shooting victims came in, a man and a woman, about two hours apart, and were quickly patched up. The man was shot twice, in a wrist and a thigh—four holes, not life-threatening. The woman was shot once in the thigh with a small entry wound but no exit wound—a stray bullet that struck her while she was walking down the street. In the trauma bay, the surgeons taped a paper clip over the entry wound so they could identify that spot on the X-ray. Goldberg wheeled the monitor over to show me the X-ray image: paper clip and bullet. “Very small,” she said, pointing to the slug, “like a .22.” As so many other patients do, the patient asked the trauma surgeons if they were going to take the bullet out, and the surgeons explained that they fix what the bullet injures, they don’t fix the bullet.

They left the wound open to prevent infection and put a dressing on it. “We’ll probably send her home tonight,” Goldberg said. “Isn’t that awful?”

She meant it as a strictly human thing. There’s no medical reason for a patient to be in a hospital longer than necessary. The point was the ridiculousness of the situation. A woman gets shot through no fault of her own, she comes to the hospital scared, and if she’s OK, Goldberg says, “It’s like, here, take a little Band-Aid.” The woman goes home, and for everyone else in the city, it’s as though the shooting never happened. It changes no policy. It motivates no law. In a perverse way, the more efficiently Goldberg does her job inside the hospital, the more invisible gun violence becomes everywhere else.

Which is why she pours so much of herself into the outreach programs, the scientific studies and any other method she has of finding control and making the problem visible. Then, as always with Goldberg, there’s call. “We care,” she told me once. “We’re gonna be here. We’re gonna be here. We’re gonna be here, and then you know what, we’re still gonna be here. And then we’re still here. That kind of thing.”

The last time I saw Goldberg, I was eating breakfast in the hospital’s basement cafeteria, one corridor away from the morgue where bodies are kept, pending transport. It was at the end of a relatively quiet overnight call shift in late March. She walked in with a coffee, looking calm and fresh. The forecast showed rising temperatures. The crust of snow on the sidewalks would soon melt, the days would lengthen, people would leave their houses to enjoy the weather. Spring was coming, and the shootings would pick back up.