Why America Needs Ebonics Now

This is how the next World War starts

Several times a week, a U.S. Air Force pilot takes off from the Royal Air Force base in Mildenhall, England, and heads for the northernmost edge of NATO territory to gather intelligence on Russia. One of these pilots is 40-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Kevin Webster, a veteran of many such expeditions and a hard guy to rattle. On a typical flight, his four-engine, silver and white RC-135 jet will rise gracefully over the old World War II bomber bases in East Anglia. It then flies over the North Sea and Denmark, taking care to remain within international airspace. When Webster reaches the Baltic Sea, the surveillance operation begins in earnest. Behind the cockpit, the fuselage of his plane is crammed with electronic equipment manned by some two dozen intelligence officers and analysts. They sit in swivel chairs, monitoring emissions, radar data and military communications harvested from below that appear on their computer screens or stream through their headphones. Inside the plane, it is chilly. The air smells faintly of jet fuel, rubber and warm wiring. The soft blue carpet helps absorb the distant thrum of the engines, and so it is also surprisingly quiet—at least until the Russians show up.

As the Polish coast fades into the distance, Webster may swing left to avoid passing directly over the heavily armed Russian base at Kaliningrad. This is where, without warning, a Russian SU-27 fighter may materialize as if out of nowhere, right outside the cockpit window, flying so close that Webster can make out the tail markings. No matter how often this happens—and lately, it has been happening a lot—these encounters always give Webster a jolt. For one thing, he and his crew can’t see the planes coming. Although his jet is carrying millions of dollars worth of the most sophisticated listening devices available to man, it lacks a simple radar to spot an incoming plane. So the only way Webster can find out what the Russian jet is doing—how close it’s flying, whether it’s making any sudden moves—is to dispatch a junior airman to crouch on the floor and peer through one of the 135’s three fuselage windows, each the size of a cereal box and inconveniently placed just below knee level.

In normal times, being intercepted isn’t a cause for concern. Russian jets routinely shadow American jets over the Baltic Sea and elsewhere. Americans routinely intercept Russian aircraft along the Alaskan and California coasts. The idea is to identify the plane and perhaps to signal, “You keep an eye on us, we keep an eye on you.” These, however, are far from normal times. Every few weeks, a Russian pilot will get aggressive. Instead of closing in on the RC-135 at around 30 miles per hour and skulking off its wing for a while, a fighter jet will careen directly toward the American plane at 150 miles per hour or more before abruptly going nose-up to bleed off airspeed and avoid a collision. Or it might perform the dreaded “barrel roll”—a hair-raising maneuver in which the Russian jet makes a 360-degree orbit around the 135’s midsection while the two aircraft hurtle along at 400 miles per hour. When this happens, there is only one thing the U.S. pilot can do: pucker up,[1] fly straight and hope his Russian counterpart doesn’t smash into him. “One false move and you may have a half second to react,” one RC-135 pilot told me.

By now, it is widely recognized that Russia is waging a campaign of covert political manipulation across the United States, Europe and the Middle East, fueling fears of a second Cold War. But it’s less understood that in international airspace and waters, Russia and the U.S. are brushing up against each other in perilous ways with alarming frequency. This problem, which began not long after Russia’s seizure of the Crimea in 2014, has accelerated rapidly in the past year. In 2015, according to its air command headquarters, NATO scrambled jets more than 400 times to intercept Russian military aircraft that were flying without having broadcast their required identification code or having filed a flight plan. In 2016, that number had leapt to 780—an average of more than two intercepts a day. There has been a similar increase in Russian jets intercepting US or NATO aircraft, as well as a significant uptick in incidents at sea in which Russian jets run mock attacks against American warships.

Russia is hardly the only source of anxiety for the Pentagon. American and Chinese ships and aircraft have clashed in the South China Sea; in early 2016, Iran seized 10 Navy sailors after their boats strayed into its waters. But senior U.S. officials view run-ins with Russia as the most dangerous, because they are part of a deliberate strategy of intimidation and provocation by Russian president Vladimir Putin—and because the stakes are so high. One false move by a hot-dogging Russian pilot could send an American aircraft and its crew spiraling 20,000 feet into the sea. Any nearby U.S. fighter would have to immediately decide whether to shoot down the Russian plane. And if the pilot did retaliate, the U.S. and Russia could quickly find themselves on the brink of open hostility.

“We are now at maximum danger,” said Admiral James Stavridis, a former commander of NATO.

With these issues in mind, I traveled to Germany this winter to talk with U.S. Air Force General Tod D. Wolters, who commands American and NATO air operations. We sat in his headquarters at Ramstein Air Base, a gleaming, modern complex where officers in the uniforms of various NATO nations bustle efficiently through polished corridors. “The degree of hair-triggeredness is a concern,” said Wolters, a former fighter pilot who encountered Soviet bloc pilots during the Cold War. “The possibility of an intercept gone wrong,” he added, is “on my mind 24/7/365.” Admiral James G. Stavridis, the commander of NATO from 2009 to 2013 and now Dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University, is more blunt. The potential for miscalculation “is probably higher than at any other point since the end of the Cold War,” he told me. “We are now at maximum danger.”

This may sound counter-intuitive, given President Donald Trump’s extravagant professions of admiration for Putin. But the strong consensus inside the U.S. military establishment is that the pattern of Russian provocation will continue—and not just because the various investigations into the Trump campaign’s links with Russia make détente politically unlikely. Antagonizing the West is central to one of Putin’s most cherished ambitions: undermining NATO. By constantly pushing the limits with risky intercepts and other tactics, Putin forces NATO to make difficult choices about when and how to respond that can sow dissension among its members.

In addition, a certain belligerence towards the U.S. is practically a political necessity for Putin. The Russian leader owes his popularity to “the tiger of patriotic mobilization,” said Leon Aron, the director of Russian studies at the American Enterprise Institute. Given the country’s diminished status in the world and its stalled economy, he added, militarized fervor for the motherland “is the only thing going for his regime.” Meanwhile,[2] since the departure of Trump’s first national security adviser, Michael Flynn, his foreign policy team is now dominated by officials who advocate a hard line on Russia.[3] For all these reasons, Philip Breedlove, who retired last summer after three years as supreme allied commander of NATO, isn’t optimistic that Russia will back off anytime soon. “We’re in a bad place and it’s getting worse rather than better,” he told me. “The probability of coming up against that unintended but strategic mess-up is, I think, rising rather than becoming less likely.” When Breedlove’s successor, General Curtis Scaparrotti, took command in May 2016, he grimly warned a gathering of diplomats and officers of a “resurgent Russia” and cautioned that NATO must be ready “to fight tonight if deterrence fails.”

All of this is happening at a time when most of the old Cold War safeguards for resolving tensions with Russia—treaties, gentlemen’s understandings, unofficial back channels—have fallen away. When a Russian jet barrel-rolls a U.S. aircraft, a senior U.S. official hops in a car and is driven to the white marble monolith on Wisconsin Avenue that houses the Russian embassy. There, he sits down with Sergey Kislyak, the ambassador who has recently attained minor fame for his surreptitious meetings with various Trump associates. A typical conversation, the U.S. official told me, goes something like this: “I say, ‘Look here, Sergey, we had this incident on April 11, this is getting out of hand, this is dangerous.’” Kislyak, the official said, benignly denies that any misbehavior has occurred. (When I made my own trip to the embassy late last year, a senior official assured me with a polite smile that Russian pilots do nothing dangerous—and certainly not barrel-rolls.)

Among the many senior officers I spoke to in Washington and Europe who are worried about Russia, there was one more factor fueling their anxiety: their new commander-in-chief, and how he might react in a crisis. After a Russian fighter barrel-rolled an RC-135 over the Baltic Sea last April, Trump fumed that the Obama administration had only lodged a diplomatic protest. He considered this to be a weak response. “It just shows how low we’ve gone, where they can toy with us like that,” he complained on a radio talk show. “It shows a lack of respect.” If he were president, Trump went on, he would do things differently. “You wanna at least make a phone call or two,” he conceded. “[But] at a certain point, when that sucker comes by you, you gotta shoot. You gotta shoot. I mean, you gotta shoot.”

One day in the mid-1980s, I stood with a cluster of American troopers on a hillside observation post near the Fulda Gap, on the border between East and West Germany. If there was going to be a war, it would come here. The Red Army would pour across the border and attempt to bludgeon the smaller U.S. and NATO forces into surrender. Each side had deployed nuclear weapons close at hand.

The soldiers at the border post were tense, serious. A few nights earlier, a man had tried to escape from the East, sprinting jaggedly across a stretch of plowed ground, somehow avoiding snipers, landmines and teams of killer dogs. The East German police shot him as he scaled a chain-link fence mere yards from the safety of West Germany. Impaled on the barbed wire, he bled slowly to death as the Americans watched in horror, his fading cries cutting through the night.

From my vantage point on top of an old concrete bunker, I looked across the misty farmland. A mile or two away were the emplacements of the Soviet Red Army. “See ‘em? Right there!” a sergeant told me. Not sure whether I was looking in the right place, I raised my hand to point. The sergeant swiftly knocked it down. “We don’t point!” he exclaimed, almost panicked. Russian and American commanders had banned such gestures, since they could so easily be mistaken for someone raising a weapon. Among troops on the front line, there was an unmistakable sense that catastrophic war was more likely to be set off by an accident than by an intentional invasion.

Looking back, it seems nothing short of miraculous that the Cold War actually remained cold. On so many occasions, misunderstandings and confusion could have erupted into mutual annihilation. One of the most frightening near-misses came in 1983, when the aging Soviet leadership in the Kremlin was convinced that an attack by the U.S. was imminent. They had been badly rattled by President Ronald Reagan’s declaration that the Soviet superpower was an “evil empire” destined for “the ash-heap of history,” and by his talk of developing a so-called Star Wars defense system capable of zapping any target from space. And so when Soviet spies began reporting on a large-scale US-NATO military exercise, code-named Able Archer, the Kremlin concluded that they were witnessing preparations for a massive conventional and nuclear offensive.

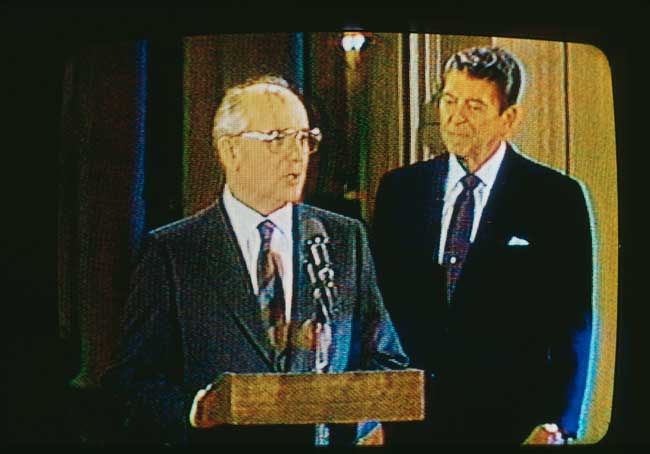

Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty on December 8, 1987. It was the first time that the two sides committed to reducing their nuclear arsenals.

(Alfred Gescheidt/Getty Images)

Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty on December 8, 1987. It was the first time that the two sides committed to reducing their nuclear arsenals.

(Alfred Gescheidt/Getty Images)

It did look like the real thing. The Pentagon sent tanks, artillery and 19,000 troops into Germany for weeks of mock combat operations. Bombers were loaded with dummy nuclear warheads in a rehearsal of procedures for transitioning from conventional to nuclear war. In Moscow, the General Staff began calling up military reserves and canceling troop leaves. Factories conducted air raid drills. Fighter and bomber squadrons were put on heightened alert. And inside the Kremlin, senior leaders considered a preemptive nuclear strike to avoid defeat, according to a top-secret U.S. intelligence report produced six years later. The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency picked up some of this, but officials simply didn’t believe the Soviets thought the U.S. intended to launch a nuclear attack. After all, they reasoned, these rehearsals were an annual event and the U.S. and NATO had even issued press releases describing Able Archer as a training exercise. They didn’t realize that in Moscow, these assurances were waved aside as lies.

The Soviets decided not to act, for reasons that remain unclear—but misunderstandings like these alarmed both sides. The U.S. and Russia together had more than 61,000 nuclear warheads, many mounted on missiles targeted at each other and on hair-trigger alert. And so, beginning in the late 1980s, the United States, Russia and their allies started developing a set of formal mechanisms for preventing accidental war. These treaties and agreements limited the size of deployed forces, required both sides to exchange detailed information about weapon types and locations and allowed for observers to attend field exercises. Regular meetings were held to iron out complaints. Russian and American tank commanders even chatted during military exercises. The aim, ultimately, was to make military activities more transparent and predictable. “They worked—we didn’t go to war!” said Franklin C. Miller, who oversaw crises and nuclear negotiations during a long Pentagon career.

And yet few of these agreements have survived Putin’s regime and the brewing animosity between Moscow and Washington. The problem, a senior U.S. official explained, isn’t that the agreements are faulty or outdated, but rather that the Russians can no longer be trusted to observe them.

The result is that the U.S and Russia are now more outwardly antagonistic than they have been in years. Since the Cold War ended in 1991, NATO has accepted 10 European countries formerly allied with the Soviet Union. In response, Russia has expanded its military; engaged in powerful cyberwar attacks against Estonia, Germany, Finland, Lithuania and other countries; seized parts of Georgia; forcibly annexed Crimea; sent its troops into Ukraine; and staged multiple no-notice exercises with the ground and air power it would use to invade its Baltic neighbors. In one such maneuver last year, Russia mobilized some 12,500 combat troops in territory near Poland and the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. According to a technical analysis by the RAND Corp., a lightning Russia strike could carry its troops into NATO capitals in the Baltics in less than 60 hours.

Last year, NATO shifted its official strategy from “assurance”—a passive declaration to stand by its allies—to “deterrence,” which requires sufficient combat power to repel armed aggression. The alliance also approved a new multinational response force, some 40,000 troops in all. In January, under a separate Obama administration initiative, the United States rushed a 4,000-strong armored brigade combat team to Poland and the Baltic states. (Lieutenant General Tim Ray, the deputy commander of U.S. forces in Europe, explained that its objective is to “to deter Russian aggression” by stationing “battle-ready” forces in forward positions.) Army engineers have started strengthening eastern European runways to accept heavier air shipments and are reconfiguring some eastern European railroads to handle rail cars carrying tanks and heavy armor. This March, a U.S. combat aviation brigade arrived in Germany with attack gunships, transport and medevac helicopters and drones, and is deploying its units to Latvia, Romania and Poland.

So far, these efforts to shore up NATO have proceeded despite the Trump administration’s occasional shows of disdain for the military alliance.[4] In late March, Scaparrotti acknowledged that he had not yet briefed the president about NATO-Russia relations. However, Trump’s secretary of defense, Jim Mattis, recently made a point of affirming that NATO is the “fundamental bedrock” of American security. Any change to that policy would be met with fierce opposition in Congress from defense stalwarts like Senator John McCain of Arizona, who is demanding that the United States use “all elements of American power” against Russia.

This February, the two top commanders of the United States and Russia met in Azerbaijan, in a rare effort to bring some stability to U.S.-Russia relations. A month later, they met again in Turkey to review a procedure to prevent accidents involving aircraft operating over Syria. But that’s a narrow issue. A broader restoration of the Cold War-era constraints on military activity seems unlikely. Increasingly, each side sees the other as an adversary. A senior Russian diplomat put the blame squarely on the United States. “We are being seen as an object to deter—as the enemy,” he told me. “In that case, how are we going to talk?”

What this means is that there are few remaining mechanisms to defuse unexpected emergencies. In testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee in late March, Scaparrotti acknowledged that he has virtually no contact with Russian military leaders. (“Don’t you think that would be a good idea?” Independent Senator Angus King of Maine queried. “If you could say, ‘Wait a minute, that missile was launched by accident, don’t get alarmed’?”) In 2014, in response to Russia’s intervention in Crimea, Congress passed a law halting almost all military-to-military communications. Even the spontaneous and informal exchanges that used to occur among Russian and American officers have largely ended.

Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, who commands U.S. Army forces in Europe, told me last year that he knew his Russian counterpart—at the time, Colonel-General Andrei Kartapolov—but had no direct contact with him. If a problem arose—say, a U.S. Special Forces sergeant serving as a trainer in Ukraine suddenly encountered a Russian commando and gunfire broke out—Hodges couldn’t have called Kartapolov to cool things off. There are no other direct lines of communication. Once, Hodges told me, he sat next to the general at a conference. He filled Kartapolov’s water glass and gave him a business card, but the gestures were not reciprocated and they never spoke.

In December 2015, a Turkish F-16 jet shot down a Russian SU-24 fighter on the Turkish-Syrian border. The Russian fighter plummeted in flames and its co-pilot was killed by ground fire. The surviving pilot, Captain Konstantin Murakhtin, said he’d been attacked without warning; Turkey insisted that the Russian plane had violated its airspace. Within days Putin had deftly turned the incident to his advantage. Instead of seeking to punish Turkey, he accused the U.S. of having a hand in the incident, without any evidence. Then he coaxed Turkey, a NATO member, into participating in joint combat operations over Syria. He also engineered Syrian peace talks in which the United States was pointedly not invited to participate. It was a bravura performance. Russia, says Breedlove, the retired NATO commander, “is playing three-dimensional chess while we are playing checkers.”

Putin’s favored tactic, intelligence officials say, is known as “escalation dominance.” The idea is to push the other side until you win, a senior officer based in Europe explained—to “escalate to the point where the adversary stops, won’t go farther. It’s a very destabilizing strategy.” Stavridis cast it in the terms of an old Russian proverb: “Probe with a bayonet; when you hit steel withdraw, when you hit mush, proceed.” Right now, he added, “the Russians keep pushing out and hitting mush.”

This mindset is basically the opposite of how both American and Soviet leaders approached each other during the Cold War, even during periods of exceptional stress such as the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. Having endured the devastation of World War II, they understood the horror that lurked on the far side of a crisis. “When things started to get too close, they would back off,” said Miller, the retired Pentagon official.

The term of art for this constant recalibration of risk is “crisis management”—the “most demanding form of diplomacy,” writes Sir Lawrence Freedman, an emeritus professor of war studies at King’s College London. Leaders had to make delicate judgments about when to push their opponent and when to create face-saving off-ramps. Perhaps most critically, they had to possess the confidence to de-escalate when necessary. Skilled crisis management, Freedman writes, requires “an ability to match deeds with words, to convey threats without appearing reckless, and to offer concessions without appearing soft, often while under intense media scrutiny and facing severe time pressures.”

A recent textbook example came in January 2016, when Iran seized those 10 U.S. Navy sailors, claiming that they had been spying in Iranian waters in the eastern Persian Gulf. President Barack Obama’s secretary of state, John Kerry, immediately opened communications with his counterpart in Tehran, using channels established for negotiating the nuclear deal with Iran. By the next morning, the sailors had been released. The U.S. acknowledged the sailors had strayed into Iranian waters but did not apologize, asserting that the transgression had been an innocent error. Iran, meanwhile, acknowledged that the sailors had not been spying. (The peaceful resolution was not applauded by Breitbart News, headed at the time by Stephen Bannon, who is now Trump’s chief White House strategist. Obama, a Breitbart writer sneered, has been “castrated on the world stage by Iran.”)

Today, thanks to real-time video, the men in the Kremlin and White House can know—or think they know—as much as the guy in the cockpit of a plane or on the bridge of a warship.

Neither Putin nor Trump, it’s safe to say, are crisis managers by nature. Both are notoriously thin-skinned, operate on instinct, and have a tendency to shun expert advice. (These days, Putin is said to surround himself not with seasoned diplomats but cronies from his old spy days.) Both are unafraid of brazenly lying, fueling an atmosphere of extreme distrust on both sides. Stavridis, who has studied both Putin and Trump and who met with Trump in December, concluded that the two leaders “are not risk-averse. They are risk-affectionate.” Aron, the Russia expert, said, “I think there is a much more cavalier attitude by Putin toward war in general and the threat of nuclear weapons. He continued, “He is not a madman, but he is much more inclined to use the threat of nuclear weapons in conventional [military] and political confrontation with the West.” Perhaps the most significant difference between the two is that Putin is far more calculating than Trump. In direct negotiations, he is said to rely on videotaped analysis of the facial expressions of foreign leaders that signal when the person is bluffing, confused or lying.

At times, Trump has been surprisingly quick to lash out at a perceived slight from Putin, although these moments have been overshadowed by his effusive praise for the Russian leader. On December 22, Putin promised to strengthen Russia’s strategic nuclear forces in his traditional year-end speech to his officer corps. Hours later, Trump vowed, via Twitter, to “greatly strengthen and expand” the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal. On Morning Joe the following day, host Mika Brzezinski said that Trump had told her on a phone call, “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.” And in late March, the Wall Street Journal reported that Trump was becoming increasingly frustrated with Russia, throwing up his hands in exasperation when informed that Russia may have violated an arms treaty.

Some in national security circles see Trump’s impulsiveness as a cause for concern but not for panic. “He can always overreact,” said Anthony Cordesman, senior strategic analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a veteran of many national security posts throughout the U.S. government. “[But] there are a lot of people [around the president] to prevent an overreaction with serious consequences.” Let’s say that Trump acted upon his impulse to tell a fighter pilot to shoot a jet that barrel-rolled an American plane. Such a response would still have to be carried out by the Pentagon, Cordesman said—a process with lots of room for senior officers to say, “Look, boss, this is a great idea but can we talk about the repercussions?”

And yet that process is no longer as robust as it once was. Many senior policymaking positions at the Pentagon and State Department remain unfilled. A small cabal in the White House, including Bannon, Jared Kushner and a few others, has asserted a role in foreign policy decisions outside the normal NSC process. It’s not yet clear how much influence is wielded by Trump’s widely respected national security adviser, Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster. When lines of authority and influence are so murky, it increases the risk that a minor incident could boil up into an unintended clash, said retired Marine Corps General John Allen, who has served in senior military and diplomatic posts.

To complicate matters further, the relentless pace of information in the social media age has destroyed the one precious factor that helped former leaders safely navigate perilous situations: time. It’s hard to believe now, but during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, for instance, President Kennedy and his advisers deliberated for a full 10 weeks before announcing a naval quarantine of the island. In 1969, a U.S. spy plane was shot down by North Korean jets over the Sea of Japan, killing all 31 Americans on board. It took 26 hours for the Pentagon and State Department to recommend courses of action to President Richard Nixon, according to a declassified secret assessment. (Nixon eventually decided not to respond.) Today, thanks to real-time video and data streaming, the men in the Kremlin and White House can know—or think they know—as much as the guy in the cockpit of a plane or on the bridge of a warship. The president no longer needs to rely on reports from military leaders that have been filtered through their expertise and deeper knowledge of the situation on the ground. Instead, he can watch a crisis unfold on a screen and react in real time. Once news of an incident hits the internet, the pressure to respond becomes even harder to withstand. “The ability to recover from early missteps is greatly reduced,” Marine Corps General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has written. “The speed of war has changed, and the nature of these changes makes the global security environment even more unpredictable, dangerous, and unforgiving.”

And so in the end, no matter how cool and unflappable the instincts of military men and women like Kevin Webster, what will smother the inevitable spark is steady, thoughtful leadership from within the White House and the Kremlin. A recognition that first reports may be wrong; a willingness to absorb new and perhaps unwelcome information; a thick skin to ward off insults and accusations; an acknowledgment of the limited value of threats and bluffs; and a willingness to recognize the core interests of the other side and a willingness to accept a face-saving solution. These qualities are not notably on display in either capital.

Revenge of the Lunch Lady

I misremember the 90s

Since we chose a retrograde misogynist to be the most powerful person on Earth, now seems like a good time to talk about sexual harassment, political correctness and how things actually get better in this country.

Thirty years ago and for a millennium or two before that, Trumpian sexual harassment was closer to the norm. Nearly everything our new president has been accused of—cornering random women and kissing them, groping employees, firing his staff for reporting their managers—was an accepted occupational hazard for women regardless of what occupation they held.

When we look back at the bad old days of sexism, we usually focus on the way attitudes have changed. And indeed they have. Most Americans, if poll numbers are any indication, find Trump’s alleged behavior repellant. The blatant, sneering “C’mere toots” sleaziness he represents hasn't disappeared, of course, but it's become less palatable, the kind of thing men have to dig up phrases like “locker room talk” to defend.

But when we tell the story of this huge (and incomplete) shift in attitudes, we tend to overlook the quieter shifts in the legal system that were just as consequential. In a 1979 case in which a woman sued three of her supervisors for harassing her, a District Court judge found that “the making of improper sexual advances to female employees [was] standard operating procedure, a fact of life, a normal condition of employment”—but still refused to award her any damages. Until 1986, the only form of sexual harassment that was illegal was quid pro quo harassment, where your boss explicitly said something like, “Sleep with me or lose your job.”

The fact that employers these days are responsible for preventing harassment, and are on the hook for millions of dollars in punitive damages if they don’t, is not a coincidence. It's the result of decades of work by women’s groups, and dozens of victims risking their livelihoods to come forward and call bullshit on the Trumpian impunity that used to be the norm.

Which brings us to a new Highline video series called “I Misremember the 90s.” Over the next few months, the series will re-examine some of the decade’s seminal events in an effort to pluck out the big ideas we missed, the figures we misunderstood and the half-truths that hardened into conventional wisdom. We hope that, by trying to understand the ’90s, we can live and think better now.

And the first episode is about the Anita Hill hearings. It’s true that they woke America up to the sleeping giant of sexual harassment. Just two years after Hill came forward to accuse Clarence Thomas of telling her about his porn habits at work, harassment cases had nearly doubled. Less than a year after the hearing, 19 women were elected to the House of Representatives and four to the Senate. The press called 1992 “The Year of the Woman.”

But that’s not the whole story. You’ve got to watch the video for that.

The blow-it-all-up billionaires by Vicky Ward

When politicians take money from megadonors, there are strings attached. But with the reclusive duo who propelled Trump into the White House, there’s a fuse.

Last December, about a month before Donald Trump’s inauguration, Rebekah Mercer arrived at Stephen Bannon’s office in Trump Tower, wearing a cape over a fur-trimmed dress and her distinctive diamond-studded glasses. Tall and imposing, Rebekah, known to close friends as Bekah, is the 43-year-old daughter of the reclusive billionaire Robert Mercer. If Trump was an unexpected victor, the Mercers were unexpected kingmakers. More established names in Republican politics, such as the Kochs and Paul Singer, had sat out the general election. But the Mercers had committed millions of dollars to a campaign that often seemed beyond salvaging.

That support partly explains how Rebekah secured a spot on the executive committee of the Trump transition team. She was the only megadonor to frequent Bannon’s sanctum, a characteristically bare-bones space containing little more than a whiteboard, a refrigerator and a conference table. Unlike the other offices, it also had a curtain so no one could see what was happening inside. Before this point, Rebekah’s resume had consisted of a brief run trading stocks and bonds (including at her father’s hedge fund), a longer stint running her family’s foundation and, along with her two sisters, the management of an online gourmet cookie shop called Ruby et Violette. Now, she was compiling lists of potential candidates for a host of official positions, the foot soldiers who would remake (or unmake) the United States government in Trump’s image.

Rebekah wasn’t a regular presence at Trump Tower. She preferred working from her apartment in Trump Place, which was in fact six separate apartments that she and her husband had combined into an opulent property more than twice the size of Gracie Mansion. Still, it quickly became clear to her new colleagues that she wasn’t content just to chip in with ideas. She wanted decision-making power. To her peers on the executive committee, she supported Alabama senator Jeff Sessions for attorney general and General Michael Flynn for national security adviser, but argued against naming Mitt Romney secretary of state. Her views on these matters were heard, according to several people on and close to the transition leadership. Rebekah was less successful when she lobbied hard for John Bolton, the famously hawkish former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, to be deputy secretary of state. And when Bolton was not named to any position, she made her displeasure known. “I know it sounds sexist, but she was whiny as hell,” says one person who watched her operate. Almost everyone interviewed for this article, supporters and detractors alike, described her style as far more forceful than that of other powerful donors.

Rebekah Mercer is rarely photographed. However, occasionally she can be found in the background of news photos, uncredited in the captions. Here she is arriving at Trump Tower on December 8, with Nick Ayers and Kellyanne Conway.

DREW ANGERER/GETTY IMAGES

Rebekah Mercer is rarely photographed. However, occasionally she can be found in the background of news photos, uncredited in the captions. Here she is arriving at Trump Tower on December 8, with Nick Ayers and Kellyanne Conway.

DREW ANGERER/GETTY IMAGES

But then the Mercers aren’t typical donors in most senses beyond their extreme wealth. (The exact number of their billions is unknown.) Robert Mercer is a youthful-looking 70. As a boy growing up in New Mexico, he carried around a notebook filled with computer programs he had written. “It’s very unlikely that any of them actually worked,” he has said. “I didn’t get to use a real computer until after high school.” Robert went on to work for decades at IBM, where he had a reputation as a brilliant computer scientist. He made his vast fortune in his 50s, after his work on predicting financial markets led to his becoming co-CEO of Renaissance Technologies, one of the world’s most successful quantitative hedge funds. A longtime colleague, David Magerman, recalls that when Robert began working at Renaissance in 1993, he and his wife, Diana, were “grounded, sweet people.” (Magerman was suspended from Renaissance in February after making critical comments about Robert in The Wall Street Journal.) But “money changed all that,” he says. “Diana started jetting off to Europe and flying to their yacht on weekends. The girls were used to getting what they wanted.”

At Renaissance, Robert was an eccentric among eccentrics. The firm is legendary for shunning people with Wall Street or even conventional finance backgrounds, instead favoring scientists and original thinkers. Robert himself, by all accounts, is extremely introverted. Rarely seen in public, he likes to spend his free time with his wife and three daughters. When, in 2014, Robert accepted an award from the Association for Computational Linguistics, he recalled, in a soft voice and with quiet humor, his consternation at being informed that he was expected to give “an oration on some topic or another for an hour, which, by the way, is more than I typically talk in a month.” Sebastian Mallaby’s account of the hedge-fund elite, More Money Than God, describes him as an “icy cold” poker player who doesn’t remember having a nightmare. He likes model trains, having once purchased a set for $2.7 million, and has acquired one of the country’s largest collections of machine guns.

For years, Robert has embraced a supercharged libertarianism with idiosyncratic variations. He is reportedly pro-death penalty, pro-life and pro-gold standard. He has contributed to an ad campaign opposing the construction of the ground zero mosque; Doctors for Disaster Preparedness, a group that is associated with fringe scientific claims; and Black Americans for a Better Future—a vehicle, the Intercept discovered, for an African-American political consultant who has accused Barack Obama of “relentless pandering to homosexuals.” Magerman, Robert’s former colleague at Renaissance, recalls him saying, in front of coworkers, words to the effect that “your value as a human being is equivalent to what you are paid. ... He said that, by definition, teachers are not worth much because they aren't paid much.” His beliefs were well-known at the firm, according to Magerman. But since Robert was so averse to publicity, his ideology wasn’t seen as a cause for concern. “None of us ever thought he would get his views out, because he only talked to his cats,” Magerman told me.

Robert’s middle daughter Rebekah shares similar political beliefs, but she is also very articulate and, therefore, able to act as her father’s mouthpiece. (Neither Rebekah nor Robert responded to detailed lists of questions for this article.) Under Rebekah’s leadership, the family foundation poured some $70 million into conservative causes between 2009 and 2014.[1] The first candidate they threw their financial weight behind was Arthur Robinson, a chemist from Oregon who was running for Congress. He was best known in his district for co-founding an organization that is collecting thousands of vials of urine as part of an effort it says will “revolutionize the evaluation of personal chemistry.” Robinson didn’t win, but he got closer than expected, and the Mercers got a taste of what their money could do. In 2011, they made one of their most consequential investments: a reported $10 million in a new right-wing media operation called Breitbart.

“I don’t know any of your fancy friends,” Robert Mercer told Sheldon Adelson, “and I haven’t got any interest in knowing them.”

That the family gravitated toward Andrew Breitbart’s upstart website was no accident. The Mercers are “purists,” says Pat Caddell, a former aide to Jimmy Carter who has shifted to the right over the years. They believe Republican elites are too cozy with Wall Street and too soft on immigration, and that American free enterprise and competition are in mortal danger. “Bekah Mercer might be prepared to put a Democrat in Susan Collins’ seat simply to rid the party of Susan Collins,” a family friend joked by way of illustrating her thinking. So intensely do the Mercers want to unseat Republican senator John McCain[2] that they gave $200,000 to support an opposing candidate who once held a town hall meeting to discuss chemtrails—chemicals, according to a long-standing conspiracy theory, that the federal government is spraying on the public without its knowledge. In short, unlike other donors, the Mercers are not merely angling to influence the Republican establishment—they want to obliterate it. One source told me that, in a meeting with Sheldon Adelson and Robert Mercer a few years ago, the casino mogul asked Robert if he was familiar with certain big Republican players. According to the source, Robert shut him down. “I don’t know any of your fancy friends,” he replied, “and I haven’t got any interest in knowing them.”

And so it seemed almost inevitable that their paths converged with Bannon’s when he took over Breitbart in 2012. The Mercers recognized Bannon as an ideological ally. They also appreciated how quickly he improved the website’s finances. Unlike many people in their orbit, Bannon wasn't obsequious: According to one person who often spends time with them, he made zero effort to dress up around his benefactors, often appearing in sweatpants and “looking almost like a homeless person.” Bannon was respectful around Robert, says this person, but with Rebekah he was more apt to say precisely what he thought: “He worked for Bob; he worked with Rebekah.”

Although the Mercers had initially been persuaded to back Texas senator Ted Cruz in the Republican primary, Bannon preferred Trump, and by the time of the Republican National Convention the Mercers were with him. Rebekah made her move last August, at a fundraiser at the East Hampton estate of Woody Johnson, the owner of the New York Jets. According to two sources, one who strategized with the Mercers and another who worked closely with Trump, Rebekah insisted on a 30-minute face-to-face meeting with Trump, in which she informed him that his campaign was a disaster. (Her family had pledged $2 million to the effort about a month earlier, so she felt comfortable being frank.) Trump, who knew her slightly, was willing to listen. He had been disturbed by recent stories detailing disorganization in his campaign and alleging ties between Trump's campaign manager, Paul Manafort, and pro-Russia officials in Ukraine. Rebekah knew of this and arrived at her meeting with “props,” says the source who strategized with the Mercers: printouts of news articles about Manafort and Russia that she brandished as evidence that he had to go. And she also had a solution in mind: Trump should put Bannon in charge of the campaign and hire the pollster Kellyanne Conway.[3]

By the following morning, Rebekah was breakfasting at Trump’s golf club in Bedminster, New Jersey, with the two people he trusts most, Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner, to talk through the proposal in more detail. Within four days, Trump did exactly as Rebekah had advised. Manafort was out. Bannon was in charge. Trump also brought on David Bossie, the president of Citizens United, with whom the Mercers and Bannon had been close for years. Less than four months later, Mercer's handpicked team had pulled off one of the greatest upsets in American politics. Through a bizarre combination of daring and luck, the insurgents had won. Now, they were Trump’s version of the establishment—which is to say, a very volatile one.

On July Fourth weekend in 2014, members of the Mercer clan (Robert, Rebekah and her husband, Sylvain Mirochnikoff) went to visit some new friends. They traveled on Robert’s 203-foot luxury superyacht, the Sea Owl, and anchored just off the WASP enclave of Fishers Island in New York’s Long Island Sound. Their destination, a medieval-style granite castle called White Caps, towered over the shoreline. This was the summer home of Lee and Alice Hanley, Reagan conservatives who’d made their fortune in Texas oil and gas but lived mostly between Greenwich, Connecticut, and Palm Beach, Florida. Like the Mercers, the Hanleys were convinced that the American political establishment was rotten to its foundations. Unlike the Mercers, though, they were popular and vigorous socialites. They loved to entertain and to act as connectors between politicians and donors in their assorted properties, even on their private jet.

That holiday weekend, Lee Hanley revisited the subject of a poll he’d commissioned in 2013 from Pat Caddell, a longtime friend. Hanley had wanted to truly understand the mood of the country and Caddell had returned with something called the “Smith Project.” The nickname alluded to the Jimmy Stewart movie “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” because its results were so clear: Americans were hungry for an outsider. It didn’t matter whether the candidate came from the left or the right; voters just wanted somebody different. They had lost all faith in the ruling class—the government, the media, Wall Street. “It showed the entire blow-up of the country coming,” Caddell told me. “A whole new paradigm developing.”

No Republican had yet emerged as a front-runner in the 2016 primary, but the Hanleys believed Ted Cruz could take Caddell’s insights and ride them all the way to the White House. They saw Cruz as a unicorn: a dedicated fiscal and social conservative who had broken with his party repeatedly. They were dismissive of Trump. “He doesn't understand politics or geopolitics or anything about the running of the government,” Alice Hanley told me recently.

Rebekah Mercer saw the Koch network as hopelessly soft on trade and immigration and was hungry for a way to promote her own more hard-line ideology.

Robert Mercer and Cruz had met before during a conference in February 2014, when Lee Hanley had invited them to the five-diamond Breakers resort in Palm Beach for a grilling session. Robert was impressed by Cruz’s intellect, according to a person at the meeting, but worried that the 43-year-old senator was too young and might struggle to capture voters’ imaginations. Still, Robert warmed to him over the course of many weekends at various Hanley homes. Apparently, Cruz can hold his alcohol (his preference is cabernet), which is a prized attribute in the Hanleys’ circle.

As the Mercers weighed whether to get involved in a presidential race, their calculus was quite different from that of other megadonors, most of whom run massive corporate empires. Various people who have worked with the Mercers on campaigns told me they didn’t pressure their candidates to adopt policies that would benefit the family’s financial interests, such as favorable regulations for hedge funds. Instead, their mission was a systemic one. Steve Hantler, a friend of Rebekah’s, says she was determined to “disrupt the consultant class,” which she saw as wasteful and self-serving. She wanted to disrupt the conservative movement, too. Rebekah saw the Koch network as hopelessly soft on trade and immigration and was hungry for a mechanism to promote a more hard-line ideology. According to Politico and other sources, she was frustrated at the time that no one was taking her seriously. As it happened, however, the family owned what seemed to be an ideal vehicle for achieving her goals.

Around 2012, Robert Mercer reportedly invested $5 million in a British data science company named SCL Group. Most political campaigns run highly sophisticated micro-targeting efforts to locate voters. SCL promised much more, claiming to be able to manipulate voter behavior through something called psychographic modeling. This was precisely the kind of work Robert valued. “There’s no data like more data,” he likes to say. Robert had made his money by accumulating piles of data on human behavior (markets might move in a certain direction when it rains in Paris, for instance), in order to make extremely precise and lucrative financial bets. Similarly, SCL claimed to be able to formulate complex psychological profiles of voters. These, it said, would be used to tailor the most persuasive possible message, acting on that voter’s personality traits, hopes or fears. The firm has worked on campaigns in Argentina, Kenya, Ghana, Indonesia and Thailand; the Pentagon has used it to conduct surveys in Iran and Afghanistan. Best of all, from the Mercers’ perspective, SCL operated entirely outside the GOP apparatus. (A source close to Rebekah said she wanted a “results-oriented” consultant.) As Rebekah saw it, SCL would allow the Mercers to control the data operation of any campaign they supported, giving the family enormous influence over messaging and strategy.

And it would be Rebekah who would actually carry out this plan. Robert preferred to focus on his work at Renaissance, often operating from his Long Island mansion, Owl’s Nest. “He wouldn’t look under the hood, because that’s not what he does,” says Bob Perkins, one of Caddell’s associates who worked on the Smith Project. Besides, Rebekah was the political animal in the family. (Her older sister Jenji has practiced law; her younger sister Heather Sue is, like Robert, a competitive poker player).

This was a relatively new phenomenon. Rebekah isn't known to have been particularly political earlier in adulthood, while gaining a master’s degree in management science and engineering from Stanford, or in early motherhood. (She has four children with her French-born husband, who became an investment banker at Morgan Stanley.) But, after the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in 2010, which significantly loosened restrictions on political spending, Rebekah decided it was time to “save America from becoming like socialist Europe,” as she has put it to several people. She started attending Koch events and donating to the Goldwater Institute, a right-wing think tank based in Arizona. The family’s political advocacy accelerated rapidly. It was in 2012 that she really attracted attention in GOP circles when, not long after Mitt Romney lost the presidential race, she stood up before a crowd of Romney supporters at the University Club of New York and delivered a scathing but detailed diatribe about his inadequate data and canvassing operation. “Who is that woman?” people in attendance asked.

With SCL, Rebekah finally had the chance to prove she could do better. The company’s American branch was renamed Cambridge Analytica, to emphasize the pedigree of its behavioral scientists. And Rebekah started flying Alexander Nix, the firm’s Old Etonian CEO, around the country to introduce him to her contacts. Nix, 41, is not a data scientist (his background is in financial services), but he is a showy salesman. Dressed in impeccably tailored suits, he is in his element on stage making presentations at large conferences. He can, however, come across as arrogant. (“I love the fact that you're telling your story, but I'm the one giving the interview,” he told me in a conversation.)

Alexander Nix at Cambridge Analytica's New York office. Rebekah Mercer was impressed by Nix's command of data and artistry on the polo field.

JOSHUA BRIGHT/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES

Alexander Nix at Cambridge Analytica's New York office. Rebekah Mercer was impressed by Nix's command of data and artistry on the polo field.

JOSHUA BRIGHT/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES

According to Perkins and Caddell, Rebekah and Nix met with them a few times to discuss how CA could use the Smith Project. Rebekah was clearly impressed by Nix. In one meeting, according to Perkins, she gushed about his polo prowess and asked him to show off cellphone photos of himself on horseback. (Nix says he doesn’t recall this meeting or others with the three. He also doesn’t remember displaying such a picture and can “think of no good reason why Bob or Pat would be interested in horses.") The political veterans were skeptical. “I didn’t understand what Nix was talking about,” Perkins told me bluntly. Caddell says he was perplexed when Nix wouldn’t show him the instruments CA used to predict voter behavior. He also thought the firm didn’t grasp the seismic shift underway in American politics. And yet to his great surprise, Bannon vouched for CA, telling Caddell its scientists were “geniuses.” Caddell knew that Bannon was beholden to the Mercers—they were, after all, Breitbart’s part-owners. According to The New York Times, however, Bannon was also vice president of CA’s board. “Even if he did not have a financial investment, he intellectually owned it, which was invaluable,” says a fellow political strategist. After he learned of Bannon’s involvement, Caddell stopped asking Bannon questions about CA.

In the end, Bannon helped seal the deal between the Mercers and Cruz, with CA as the glue. In the fall of 2014, Toby Neugebauer, a garrulous oil-and-gas billionaire from Texas, took Cruz and his campaign manager, Jeff Roe, to the “Breitbart Embassy,” the website’s Washington headquarters near the Capitol. Bannon flitted in and out. Nix, as usual, did most of the talking. After Neugebauer and Roe visited SCL’s London headquarters, the Cruz team agreed that CA could play a key role in their operation, running models and helping with research. However, it was made clear to Rebekah and Nix that the entire data analytics operation would be supervised by Chris Wilson, CEO of the research firm WPA. A source close to Cruz told me that Wilson’s operation had played a crucial role when Cruz ran for the Senate with only 2 percent name recognition in Texas and defeated a far better-known opponent. Why, then, was CA necessary at all? “No one ever said directly that the quid pro quo for hiring CA was that the Mercers would support Cruz,” says someone close to Roe. Nevertheless, after CA was engaged, Neugebauer took a private jet to the Bahamas to meet Robert Mercer on the Sea Owl. When Neugebauer asked him to donate to Cruz’s bid, Robert was matter-of-fact. The family would start with $11 million.

All modern political campaigns have to balance their need for exorbitant sums of money with the obsessions of the people who want to give them that money. Roe, the straight-talking manager of the Cruz operation, has observed that running a campaign is like trying to solve a Rubik’s cube of complicated personalities and uncomfortable dependencies. He has also told people that he is careful not to get too close to the donors who make his campaigns possible, because they can be so easily annoyed by the most trivial of things—his laugh, for instance, or the way he eats a bread roll.

In the case of the Cruz campaign, the donor obsession in question was Cambridge Analytica. And it wasn’t long before Roe and his team suspected that Nix had promised them a more impressive product than he could deliver. On March 4, 2015, Cruz, Roe, Wilson and others gathered in the Hyatt in Washington D.C. for an all-day meeting with Nix and a group of CA senior executives. Wilson took notes on his computer. According to multiple members of the Cruz team, Wilson was dismayed to learn that CA’s models weren’t fully ready for his focus groups the following week. As far as the team could tell, the only data CA possessed that the campaign didn’t already have appeared to be culled from Facebook. In addition, they recalled, CA hadn’t set itself up with Data Trust, the Republican National Committee’s repository of voter information. At one point, they recall, Nix explained that the National Rifle Association’s database of members would be a valuable way to target donors. Wilson typed an emoji with rolling eyes next to the statement because it was so obvious. He told people that he came away thinking, “Red flag, red flag, red flag.”

In response to an extensive set of questions, Nix disputed this account of the meeting. He denied that Cambridge Analytica had obtained any data via Facebook—a source of controversy for the firm ever since The Guardian reported in 2015 that CA based its data on research “spanning tens of millions of Facebook users, harvested largely without their permission.” Nix also claimed that it was the Cruz team that didn’t have access to the RNC’s Data Trust for much of the cycle and that “all data used for the majority of the campaign was provided by Cambridge Analytica.” However, Mike Shields, then the RNC’s chief of staff and Data Trust’s senior adviser, told me the Cruz campaign was in fact the second to sign an agreement with Data Trust, in 2014.

Meanwhile, the red flags kept coming. Wilson found the data scientists that CA sent to Houston to be highly efficient at the day-to-day work of his research operation. But according to Cruz staffers, when he began to test CA’s specialized models, he found that they were notably off, with, for example, some male voters miscategorized as women. In phone surveys, staffers said, CA’s predictions fell short of the 85 percent accuracy the campaign expected. (“Different models have differing levels of accuracy,” Nix said in his response. “I suspect these numbers have been taken out of context to make us look bad. In many previous articles the Cruz campaign have highly rated the quality of our data scientists.”) By September, CA’s first six-month contract was up. A CA employee in the campaign’s Houston office accidentally left the invoice in the photocopier, and Wilson happened to fish it out. The invoice totaled an eye-popping $3,119,052 for work that Wilson estimated to be worth $600,000 at most. “I can’t fucking believe it,” Wilson told Roe, who concurred.

Jeff Roe (left) with Ted Cruz (right), who ultimately fell out of Rebekah Mercer's favor. “We felt to some extent she was being manipulated by Bannon," a Cruz adviser said.

ETHAN MILLER/GETTY IMAGES

Jeff Roe (left) with Ted Cruz (right), who ultimately fell out of Rebekah Mercer's favor. “We felt to some extent she was being manipulated by Bannon," a Cruz adviser said.

ETHAN MILLER/GETTY IMAGES

Nix disputed this account too, noting that the firm’s fee was “clearly stated in our statement of work and contract.” However, a former consultant for the campaign, Tommy Sears, attended budget meetings “for two if not three days” over the matter. “There was an understanding between both parties that the totality of the contract through March 2016 would be $5.5 million,” he says. “The heartburn felt by the Cruz team was that over $3 million had already been spent by September 1, 2015.”

When the Cruz team decided not to pay the full $3 million, bedlam ensued. A phone call was scheduled with Rebekah, Bannon and CA’s attorney. “I understand she’s a nice lady,” Wilson says politely of Rebekah. According to multiple people on the call, she accused Wilson of undermining CA. Bannon, meanwhile, unleashed a torrent of profanities at the Cruz team. Someone on the call gave me a censored version of his outburst: “The only reason this campaign is where it is right now is because of our people and I. My recommendation to the Mercers is just to pull them out of there and we’ll have them on another campaign by Monday.” Bannon’s language was so foul it was difficult to listen to, says one person on the call who had never met him before. Another of the political pros, who knew Bannon well, wasn’t shocked. “That’s Steve doing business,” he says.

The Cruz team was taken aback by Rebekah’s reaction. Some even wondered if she’d been given all the facts. One person who was close to the campaign says, “She is somewhere between the daughter of a brilliant hedge fund manager and mathematician and somebody who runs a bakery in New York. She clearly has a skill set, but the skill set we’re discussing here regarding the understanding of the value of data and analytics doesn’t fall into that area. She is operating under the information she’s been given.”

“If Rebekah Mercer was broke and wasn’t a major donor in the Republican party,” says a Cruz adviser, “nobody would spend two seconds trying to know her… She’s not fun. She’s just like a series of amoeba cells.”

The two sides were also diverging ideologically. In the summer of 2015, according to two sources, Rebekah reprimanded Cruz for an April article he’d co-authored with House Speaker Paul Ryan in The Wall Street Journal in support of free trade. She and Bannon told Cruz that he should adopt the positions of Jeff Sessions, whose views on trade and immigration were more in line with the conservative base. By this time, Cruz and his team were becoming increasingly concerned about Bannon’s relationship with Rebekah. Bannon (who declined to comment for this article) was now blatantly pro-Trump. Over the course of the primary, Breitbart would publish around 60 pieces disputing that Cruz was eligible to be president because he had been born in Canada. Cruz repeatedly called Rebekah to complain, but she insisted that she had to be “fair and impartial.” One of his advisers says, “We felt to some extent she was being manipulated by Bannon.” A person close to Bannon counters: “There's absolutely no way anyone could manipulate Rebekah Mercer."

After the first debate in South Carolina, Rebekah gave Cruz a “dressing down” on his performance, according to three sources. “Given what was going on around him—and what he must have truly felt—he behaved like an absolute gentleman,” says a person close to Cruz. Rebekah was incensed that Trump had a tougher immigration policy than Cruz did—she particularly liked Trump’s idea for a total ban on Muslims. Subsequently, Cruz proposed a 180-day suspension on all H1-B visas.

Meanwhile, even though the Cruz staffers generally got along well with their CA counterparts—they sometimes took the visitors country-western dancing —the firm remained a source of friction. In retrospect, Wilson told people, he believed that Nix resented the campaign for allocating work through a competitive bidding process, rather than favoring CA. Two weeks before the Iowa caucuses, Wilson assigned a contract to a firm called Targeted Victory. CA then locked its data in the cloud so it couldn’t be accessed by Roe’s team. The data remained unavailable until, a Cruz campaign source said, it was pretty much too late to be useful. Cruz won the Iowa caucuses anyway.

The Cruz operation became so fed up with Nix that they pushed back, hard, on CA’s bill for its second six-month contract. Wilson was able to negotiate the fees down after, as Cruz staffers recalled, a CA representative accidentally emailed him a spreadsheet documenting the Houston team’s salaries. (Nix said CA had intended to send the spreadsheet.) Still, the campaign wound up paying nearly $6 million to CA—which represented almost half of the money the Mercers had pledged to spend on Cruz’s behalf.

The acrimony lingered long after Cruz exited the race in May. When he decided not to endorse Trump at the GOP convention, the Mercers publicly rebuked him. In a statement, Cruz was diplomatic: “We were delighted to work with Cambridge Analytica, they were a valuable asset to my campaign, and any rumors to the contrary are completely unfounded.” (The source close to Rebekah added, “I was with Rebekah the other day and Ted Cruz was falling all over her. It’s not fair to blame CA's methodology for Cruz's loss.”) Others from Cruz’s team, however, remain bitter about the whole experience. “If Rebekah Mercer was broke and wasn’t a major donor in the Republican Party,” says one, “nobody would spend two seconds trying to know her. … She’s not fun. She’s just like a series of amoeba cells.”

One of the great challenges in reporting this story was that almost every single person in Trump’s orbit claims sole credit for his extraordinary victory on November 8. The multiplying narratives of his win can be difficult to untangle, but it is true that his operation ran somewhat more smoothly after Rebekah Mercer helped to replace Manafort with Bannon. This wasn’t necessarily because Bannon himself was a particularly deft manager—he much preferred to focus on big-picture strategy, especially Trump’s messaging in rallies. Most of the details were left to his deputy, David Bossie—at least until October, when Bossie and Trump got into an argument over Trump’s impetuousness on Twitter and Bossie was kicked off the campaign plane, according to multiple sources. But one undeniable benefit of having Bannon in charge was that Rebekah trusted him.

Bannon, several sources said, can be charming when he chooses to be. And he has a record of successfully cultivating wealthy patrons for his various endeavors over the years. At the same time, certain of his ventures have involved high drama. The most spectacular example is the Biosphere 2, a self-contained ecological experiment under a giant dome in the Arizona desert that was funded by the billionaire Texan Ed Bass. Hired as a financial adviser in the early 1990s, Bannon returned in 1994 and used a court order to take over the project, following allegations that it was being mismanaged. He showed up one weekend along with “a small army of U.S. marshals holding guns, followed by a posse of businessmen in suits, a corporate battalion of investment bankers, accountants, PR people, and secretaries,” according to a history of the project called Dreaming the Biosphere. In an effort to thwart Bannon’s takeover, some of the scientists broke the seal of the dome, endangering the experiment.

Because of his relationship with the Mercers, Bannon was able to avoid some of the tensions over Cambridge Analytica that had plagued the Cruz campaign. Before taking the job, he phoned Brad Parscale, a 41-year-old San Antonio web designer who had made websites for the Trump family for years. Although Parscale had never worked in politics before, he now found himself in charge of Trump’s entire data operation. According to multiple sources, Parscale told Bannon that he had been hauled into an unexpected meeting with Alexander Nix earlier that summer. Parscale, who is fiercely proud of his rural Kansas roots, immediately disliked the polished Briton. He informed Nix he wasn’t interested in CA’s psychographic modeling. Parscale and Bannon quickly bonded, seeing each other as fellow outsiders and true Trump loyalists. Bannon told Parscale: “I don't care how you get it done—get it done. Use CA as much or as little as you want.” Parscale did ultimately bring on six CA staffers for additional support within his data operation. But he had his own theory[4] of how Trump could secure victory—in the final weeks, he advised Trump to visit Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan, three states no one thought Trump could take. The campaign never used CA’s psychographic methodology, as a CA staffer who worked on the campaign later publicly acknowledged at a Google panel.

For the most part, Rebekah kept a low profile during the last phase of the election. On the few occasions that she appeared at Trump Tower, she sat in Bannon’s 14th-floor office. “Most people had no idea who she even was,” says one person who was there regularly. “The idea that she was on the phone to Trump or anyone all the time, that’s nonsense,” says a different source from the transition. The Mercers did intervene when a tape surfaced of Trump bragging to NBC’s Billy Bush about sexually assaulting women—by making a rare statement in Trump’s defense. In a statement to The Washington Post, they said: “If Mr. Trump had told Billy Bush, whoever that is, earlier this year that he was for open borders, open trade and executive actions in pursuit of gun control, we would certainly be rethinking our support for him. …. We are completely indifferent to Mr. Trump’s locker room braggadocio.”

Bannon in the East Wing of the White House on January 22, with Mercer (uncredited) in the background.

ANDREW HARRER-POOL/GETTY IMAGES

Bannon in the East Wing of the White House on January 22, with Mercer (uncredited) in the background.

ANDREW HARRER-POOL/GETTY IMAGES

On election night at Trump Tower, Robert Mercer was nowhere to be seen. Rebekah was in Bannon’s office. Staffers and Trump children wandered in and out of Parscale’s office, because he was usually the first person to have any actual information. Parscale, unlike almost everyone else, including Trump’s children, was convinced his boss was going to win. Trump himself remained glued to the television, refusing to believe anything until victory was officially declared. No one I talked to recalls where Rebekah was in the blur of the celebration.

But people certainly remember her presence during the transition. One night, Rebekah called Trump and told him he absolutely had to make Bannon his White House chief of staff. Trump himself later described the phone call—in a manner an observer characterized as affectionately humorous—to a crowd of about 400 people at the Mercers’ annual costume party at Robert’s mansion on December 3. This year’s theme: “Heroes and Villains.” A guest recalls that Rebekah was dressed in something “that fitted her very well, with holsters.” To the gathering, Trump recounted being woken up at around midnight— Rebekah told friends it was around 10 p.m.—and being bewildered by the late-night tirade. “Rebekah who?” he eventually asked. Everyone laughed,” says the observer. As it happened, Bannon didn’t actually want to be chief of staff, believing himself to be ill-suited to the role. He was named chief strategist instead.

Rebekah had more than personnel decisions on her mind, however. She was particularly focused on what was referred to on the transition as the “outside group.” After the election, it was widely agreed that the GOP needed a nonprofit arm, supported by major donors, to push the president’s agenda across the country, much as the Obama team had set up Organizing for America in 2009. The most important component of any organization like this is its voter database, since it can be used to seek donations and mobilize supporters behind the president’s initiatives. Rebekah wanted CA to be the data engine, which would essentially give her control of the group. And if the venture were successful, she would have an influence over the GOP that no donor had ever pulled off. Theoretically, if the president did something she didn’t like, she could marshal his own supporters against him, since it would be her database and her money. A friend of Rebekah explains: “She felt it was her job to hold the people she’d got elected, accountable to keep their promises.”

“I’m expecting to be fired by the summer,” Bannon has told friends.

On December 14, there was a meeting to discuss the outside group in a glass-walled conference room on the 14th floor of Trump Tower. Brad Parscale sat at the head of the table. Around him were roughly 12 people, including Rebekah; Kellyanne Conway; David Bossie; Michael Cohen, Trump’s lawyer; Jason Miller, then Trump’s senior communications adviser; and Marc Short, Mike Pence’s senior adviser. Parscale was known to be livid that Alexander Nix had gone on a PR blitz after the election, exaggerating CA’s role. Even worse, Parscale had heard that Nix had been telling people, “Brad screwed up. We had to rescue Brad.” (Nix denied this, saying, “Brad did a brilliant job.”)

And so when Rebekah pushed for CA to run the new group’s data operation, Parscale pushed back. “No offense to the Mercers,” he said, according to multiple attendees. “First, this group is about Trump, not about the Mercers. Second, I don’t have a problem with hiring Cambridge, but Cambridge can’t be the center of everything, because that’s not how the campaign ran.” (He did, however, suggest that Rebekah be on the board.) “No offense taken,” Rebekah replied.

But she would subsequently complain about the exchange to Bannon and others, and continued to lobby for CA to be at the center of the new organization. The situation became so testy that before the inauguration, Jared Kushner brought in Steve Hantler, Rebekah’s friend, to referee. Hantler, a quiet, gentlemanly sort, proposed that the venture be led by someone he knew would be acceptable to both sides: Nick Ayers, a senior adviser to Pence. The “outside group” is now named America First Policies. Parscale is a member, and its first national TV ads have appeared. Ayers has also been cultivating a friendship with Donald Trump Jr., who, sources say, may eventually want to lead the group himself.

The Mercers, however, have withdrawn completely. When it came to the question of whether America First should employ CA, it was Parscale’s view that prevailed: CA has no role in the group at all. “Tens beat nines in poker,” says someone involved with the formation of America First, meaning that Parscale’s close rapport with the Trump family carried greater weight than Rebekah’s connection with Bannon. Rebekah’s relationship with Jared and Ivanka is said to be diminished. Nearly every person I spoke to—Trump supporters, Cruz supporters, fellow donors, friends of Rebekah—agreed on one point: to regain some of her standing, she should fire Alexander Nix. (“We are hoping that she reads your piece and does it,” says a person she works with closely.)

On December 19, Rebekah attended a memorial service in Palm Beach for Lee Hanley, who had died four days before the election. Someone who spoke to her there was expecting her to be thrilled about the election and the position she now occupied. Instead, Rebekah was very low, says this person. She complained about John Bolton being passed over.[5] She was also said to be furious at the appointment of Mitt Romney’s niece, Ronna Romney McDaniel, to chair the RNC: To Rebekah, McDaniel personified the very GOP establishment that her family had worked so hard to cast out. “She was emotional,” says the person who was there. “She was talking about how there's no rhyme or reason to the people he's appointing, and that Ivanka was acting like first lady, and Melania was very upset about it.” When asked about this, a person very close to Rebekah said, "She thinks Ivanka is wonderful and amazing and she thinks Melania is wonderful and amazing. She's very policy-oriented and not involved in personalities.”

In the end, Rebekah Mercer’s mistake was that she thought she could upend the system and then control the regime she had helped to bring to power. Helping to elect a president wasn’t enough: She wanted the machinery to shape his presidency. Instead, the chaos simply continued. An administration full of insurgents, it turns out, functions in a near-constant state of insurgency.

Bannon is said to be exhausted and stretched. He is largely responsible for the relentless pace of initiatives and executive orders in the early weeks of the administration, because he doesn’t expect to be in the White House forever. “I’m expecting to be fired by the summer,” he has told friends, likening himself to Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister, who was instrumental in enforcing Britain’s Reformation but ended up being beheaded by his boss. A source close to Bannon says that he may have “joked about being fired,” but disagreed that Bannon is tired: “I don't think he even thinks in those terms. He is used to an intense schedule.” His focus, the source says, “is working for the president to deliver on the promises to the American people for the first 100 days and then beyond on the overall agenda of Making America Great Again.” Bannon returns Rebekah’s phone calls when he can. But, according to someone who knows both well, “relations are strained.” Another person who works with both of them says, “I think Bannon, once he finally built a relationship with Trump, didn't need Rebekah as much … and he doesn't care about that. He only cares about the country.” The source close to Bannon says that Rebekah and the chief strategist remain “close friends and allies.”

As this piece was going to press, several sources warned me not to count Rebekah out. She still has a stake in Breitbart, which holds tremendous sway over Trump’s base and has recently gone on a no-holds-barred offensive against the GOP health care plan. And on March 13, Politico reported that some Trump officials were already disillusioned with America First, which they felt had been slow to provide much-needed cover for his policy initiatives. There was talk of turning instead to a new group being launched by Rebekah Mercer. And so she may yet get another chance to realize her grand ambitions. “She’s used to getting everything she wants, 100 percent of the time,” says another person who knows her well. “Does she like getting 90 percent? No.”

The Epidemic of Gay Loneliness

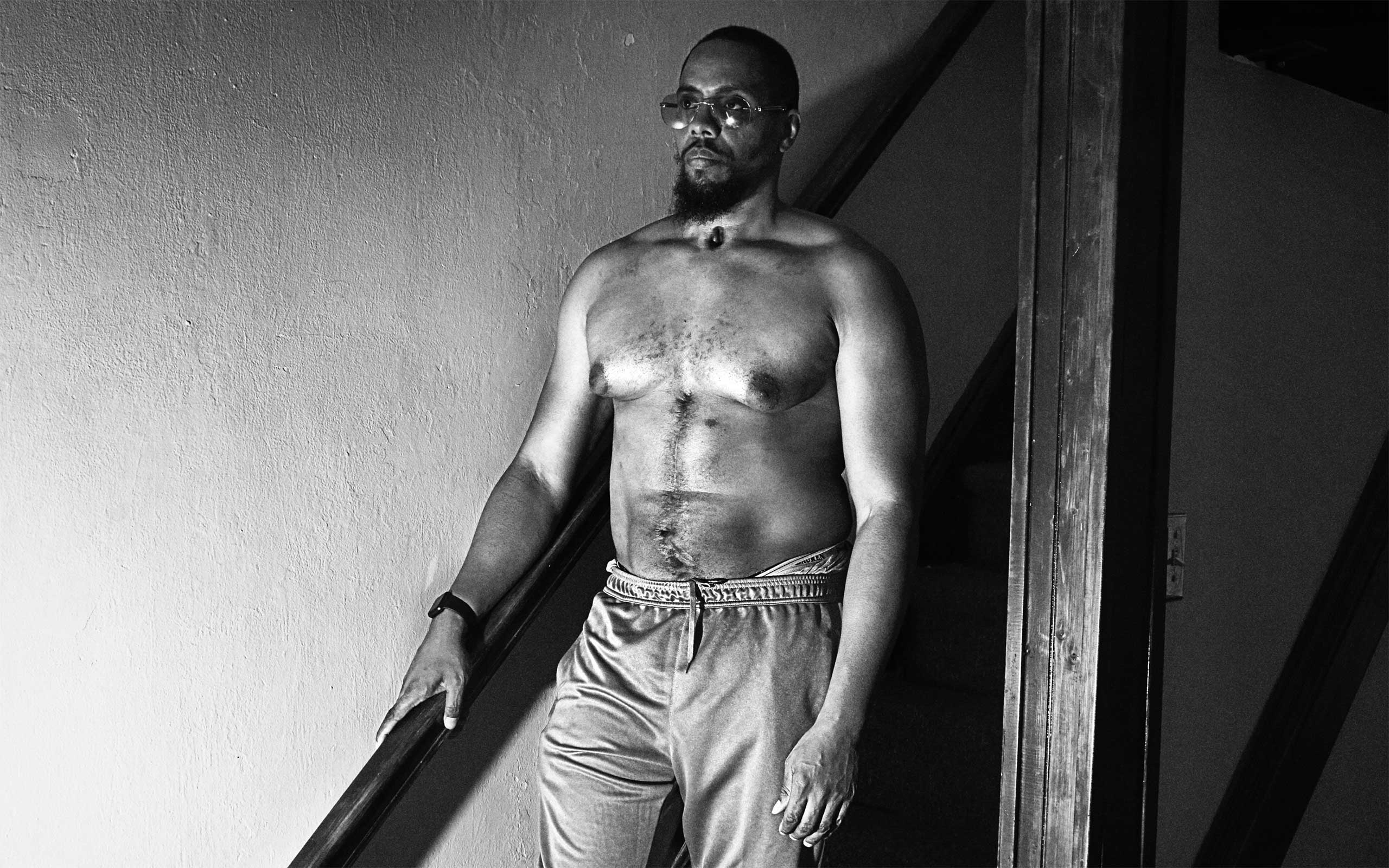

“I used to get so excited when the meth was all gone.”

This is my friend Jeremy.

“When you have it,” he says, “you have to keep using it. When it’s gone, it’s like, ‘Oh good, I can go back to my life now.’ I would stay up all weekend and go to these sex parties and then feel like shit until Wednesday. About two years ago I switched to cocaine because I could work the next day.”

Jeremy is telling me this from a hospital bed, six stories above Seattle. He won’t tell me the exact circumstances of the overdose, only that a stranger called an ambulance and he woke up here.

Jeremy is not the friend I was expecting to have this conversation with. Until a few weeks ago, I had no idea he used anything heavier than martinis. He is trim, intelligent, gluten-free, the kind of guy who wears a work shirt no matter what day of the week it is. The first time we met, three years ago, he asked me if I knew a good place to do CrossFit. Today, when I ask him how the hospital’s been so far, the first thing he says is that there’s no Wi-Fi, he’s way behind on work emails.

“The drugs were a combination of boredom and loneliness,” he says. “I used to come home from work exhausted on a Friday night and it’s like, ‘Now what?’ So I would dial out to get some meth delivered and check the Internet to see if there were any parties happening. It was either that or watch a movie by myself.”

1. That’s not his real name. Only a few of the names of the gay men in this article are real.

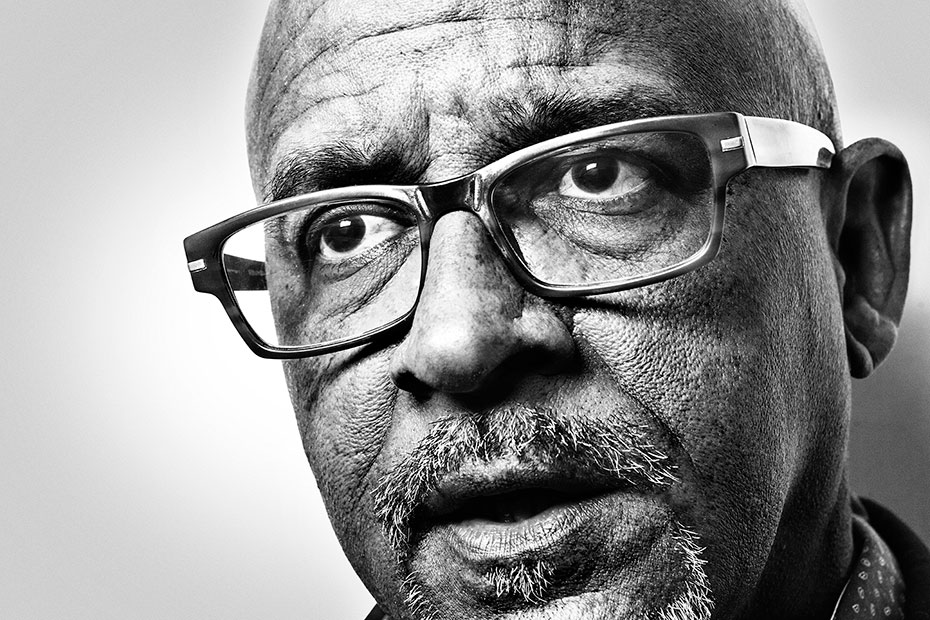

Jeremy[1] is not my only gay friend who’s struggling. There’s Malcolm, who barely leaves the house except for work because his anxiety is so bad. There’s Jared, whose depression and body dysmorphia have steadily shrunk his social life down to me, the gym and Internet hookups. And there was Christian, the second guy I ever kissed, who killed himself at 32, two weeks after his boyfriend broke up with him. Christian went to a party store, rented a helium tank, started inhaling it, then texted his ex and told him to come over, to make sure he’d find the body.

1. That’s not his real name. Only a few of the names of the gay men in this article are real.

For years I’ve noticed the divergence between my straight friends and my gay friends. While one half of my social circle has disappeared into relationships, kids and suburbs, the other has struggled through isolation and anxiety, hard drugs and risky sex.

None of this fits the narrative I have been told, the one I have told myself. Like me, Jeremy did not grow up bullied by his peers or rejected by his family. He can’t remember ever being called a faggot. He was raised in a West Coast suburb by a lesbian mom. “She came out to me when I was 12,” he says. “And told me two sentences later that she knew I was gay. I barely knew at that point.”

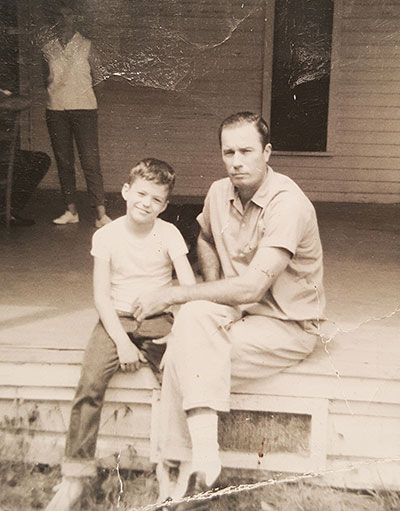

This is a picture of me and my family when I was 9. My parents still claim that they had no idea I was gay. They’re sweet.